ALL ABOUT ME 37

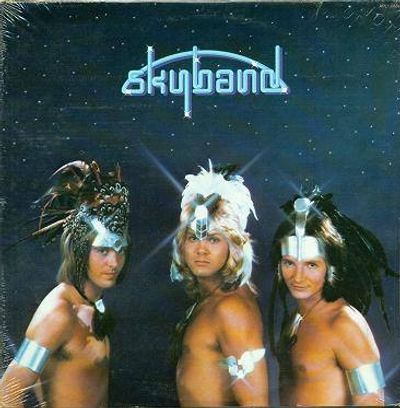

Reed and the Prelude to Player

Upon leaving the Grass Roots in 1975, I took a bit of time off to detox from the rigors of touring. During that hiatus, I took some badly-needed personal time to relax and, in the process, build a huge radio-controlled airplane. At the point of realizing it was time to return to work, I received a phone call from Warren Entner, formerly an original member of the Grass Roots who left the group at about the same time I did. Warren had invested in a company called GTO, out of England, that had set up offices on Beverly Boulevard in the ICM Building in West Hollywood. Warren had joined ranks with David Joseph, who headed up GTO. I agreed to join in on a meeting with what was left of a band known as Skyband. I went to their offices at the ICM Building and met David Joseph and two of the members of Skyband, Peter Beckett and Steve Kipner. Warren had mentioned that Skyband had been signed to a multi-album deal with RCA records. I was to replace Lane Caudell in the three-man band. The group, to the best of my recollection, still had another album to complete in order to fulfill its obligations to RCA. I began to feel somewhat uncomfortable with David Joseph, as he continuously flipped his Dunhill cigarettes and matching Dunhill lighter on the table and staring me down, making the situation feel uncomfortable. He was talking down to me. “Yes, you were lead guitar player in the Grass Roots,” he said, “but here is an opportunity to really shine.” Becoming increasingly ill at ease, I asked Mr. Joseph, “What would be my financial participation with the group?” To my surprise, if I recall correctly, as I glanced at Steve and Peter, I was told that the group had accumulated a $380,000 deficit. After a moment or two of thought, I looked at David Joseph and asked, “Does this mean that I would be equally involved in debt?” To my astonishment, his answer was an arrogant “Yes.”

ALL ABOUT ME 38

Reed and the Prelude to Player (2)

At that point, I looked around the room, thanked Warren (who even today I still consider a good friend) for thinking of me as a possible colleague in this venture. Then I looked at David Joseph and said, “I don’t think this is for me.” I thanked him and stood up. We shook hands, and I made my way to the elevator. Waiting for the elevator, I heard the thumping of footsteps behind me. I turned around, and to my surprise, saw Steven and Peter approaching me. They then proceeded to say, “Mate, what do you know that we don’t know?” I replied, “You guys are really in debt, and I just don’t want to share your debt.” I added, “I live down the street from here; if you want to get together, we can sit down and talk.” They accepted my invitation and agreed to meet later that afternoon at my house on Lloyd Street in West Hollywood.

ALL ABOUT ME 39

Reed and the Prelude to Player (3)

Peter and Steve showed up. They sat down with an inexpensive bottle of Almandine wine, and had a few. After discussing the situation further for a while, we got kind of tired and proceeded to pick up an acoustic guitar and started fooling around. It’s pleasing to note that we really did enjoy each other’s company. But reality set in. They came to realize that they were stuck in a solid contract. I had a friend who was an attorney. His name was Bruce Grakel. Bruce had clients such as Jimmy Webb, Harry Nilsson, and Ringo Starr, just to name a few. My wife at the time, Patty, got to know Bruce and his wife Ronnie well and socialized often. On one occasion when we were together, I happened to tell Bruce about the situation that Peter and Steven faced with GTO. Being the good friend that Bruce was, he assured me that he would investigate the matter from a legal perspective.

ALL ABOUT ME 40

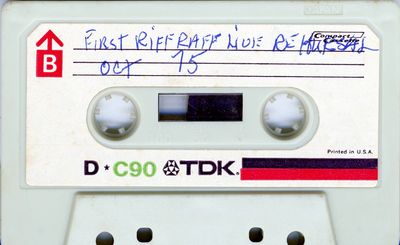

Reed and the Prelude to Player (4)

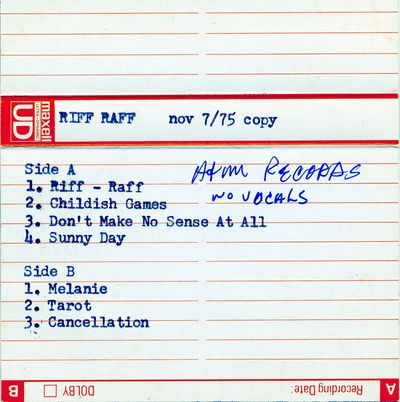

After some legal maneuvers, we did find a legitimate and ethical way to move forward, and Steve Kipner, Peter Beckett, and I succeeded in creating a viable band, under its first name Riff Raff. On a daily basis, Riff Raff rehearsed tunes written by members of the band. Steve’s song was Square Peg in a Round Hole, Peter’s song was Childish Games (Foolish Pride). We began composing additional original material while rehearsing at the famous Whiskey-a-Go-Go on Sunset Boulevard. In my possession, I still have the rehearsal tapes of Riff Raff as well as the basic tracks that were recorded at A&M Studios on La Brea and Sunset. The band had progressed to the point where instead of sending cassettes to prospective producers’ offices as was customary, we literally went in and performed as a trio, using acoustic guitars and small amps. We performed live for such people as Bill Halverson, engineer for Crosby, Stills, and Nash at his home, and Phil Ramone, producer of Paul Simon and Billy Joel. Steve Kipner was still part of the deal when we performed for Bill Halverson. Steve left the band, and J.C. Crowley, who was living in his car at the time, moved into my house and lived with my wife Patty and me.

ALL ABOUT ME 41

Reed and the Prelude to Player (5)

With Crowley aboard, we had been scheduled to meet with Steve Barri. We actually met and performed for Phil Ramone at ABC Dunhill Studios on Beverly Boulevard. We sat down in the studio and played acoustically for him. Original songs included Cancellation, Love Is Where You Find It, and Movin’ Up. Phil Ramone tended to gravitate toward J.C.’s songs, which did not go over well with Peter. That was the first moment I realized Peter’s desire to control the group. He seemed to have a sense of possession over it. Needless to say, things did not work out well with Phil Ramone. At about this same time, we discovered that another band out of England on the RCA label had ownership of the Riff Raff name. This fact caused us to change the name of our band to Bandana.

I had a talk with Ronnie, attorney Bruce Grakel’s wife, and mentioned the frustration I was experiencing. Ronnie talked to Bruce, who was negotiating a record label deal for Dennis Lambert and Brian Potter, both of whom were previous songwriters for the Grass Roots. An audition was set up through Ronnie and Bruce Grakel and the existing negotiator Bob Ellis, who met with Dennis and Brian. A six-song singles deal was negotiated, and we signed with Haven Records. Such songs as Melanie, written by J. Crockett but lead vocals by P. Beckett; Love Is Where You Find It, written by J. Crockett, J.C. Crowley and myself but lead vocals by Peter Beckett and J.C. Crowley; Movin’ Up, written by J. Crockett, Steve Kipner, and myself but lead vocals by P. Beckett; and Cancellation, written by J. Crockett, S. Kipner, and myself but vocals by P. Beckett. Peter Beckett had maneuvered around his prior commitment to GTO by changing his name to J. Crockett.

The deal was done. There was a single released, Jukebox Saturday Night, written by J.C. Crowley and Peter Beckett. The flip side was Love Is Where You Find It. Needless to say, the single didn’t chart.

ALL ABOUT ME 42

Reed and the Prelude to Player (6)

At that juncture, the band became pretty difficult. Peter Beckett and J.C. Crowley were not consummate live performers. On the other hand, I was. During one road trip, set up by the now-defunct Bob Ellis and Associates taken over by the Palmer Roswell Company, we were sent off to perform a live show somewhere in Texas, I believe. I remember sharing a hotel room with a leaking roof; but the anxiety over the Peter Beckett and J.C. Crowley situation was just too much for me to handle. Things continued to deteriorate, and both Peter Beckett and J.C. Crowley decided in their own minds that I was no longer in the band. I recall walking to SoundLab Studios, where Gary Wright had just finished recording Dream Weaver. We were finishing up some songs. Through the studio glass, I saw Peter and J.C. at the piano in the studio along with Lambert and Potter, our producers, repeatedly doing the melody of the tune Baby, Come Back. I had a creepy feeling at that time, since this was going on behind my back. I remember walking out into the parking lot and saying to myself, “I think this gig is up.” Peter had gotten his way.

That evening, my wife Patty and I were at home, sitting around the dining room table. Paul Palmer, who was part of the Palmer Roswell Management Company and a good man who I really admire a lot to this day, informed me that J. C. Crowley and Peter Beckett had decided my services were no longer required for the band. I said to Paul, “Tell them both good luck; they’re really going to need each other.” Then later I got angry. At that point, Player was over. Patty and I separated some time later.

ALL ABOUT ME 43

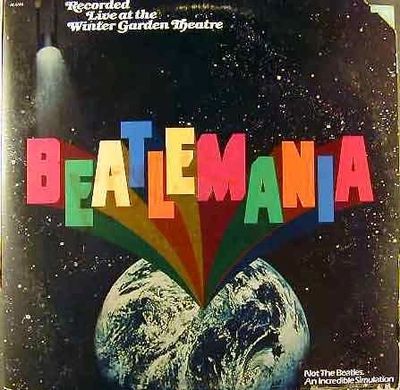

Reed and Broadway Beatlemania

Like a savior, my ex-wife Patty called me and said, “Radio station KROK has been promoting a show called Beatlemania. That show holds a strong potential for going to Broadway at the Winter Garden Theatre in New York. They’re coming to Los Angeles to audition Beatle sound-alikes; but most important, the hardest role to fill is Paul McCartney.” Patty continued, “You’re a dead ringer for this. Go for it.” To this day, I thank Patty for getting me out of the Player nightmare and helping me move on in life. I listened to KROK intently to find out where and when auditions would be held.

ALL ABOUT ME 44

Reed and Broadway Beatlemania (2)

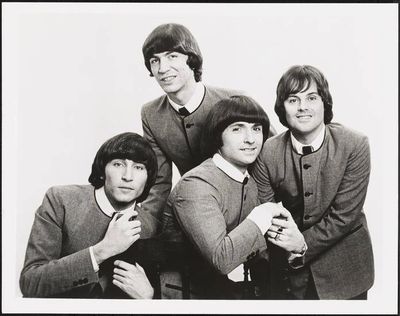

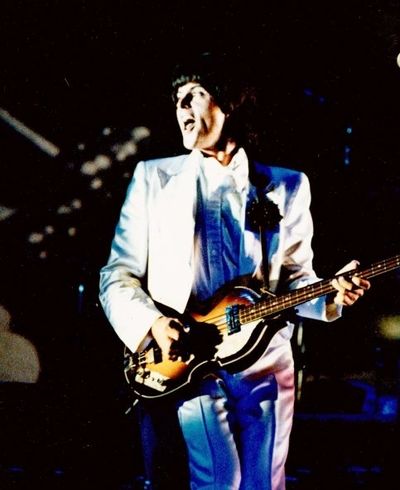

Auditions were held at Studio Instrument Rentals (SIR), the number-one rehearsal spot in Los Angeles at the time. I showed up on the designated day. It was very hot day in the mid afternoon. I walked to a very large, dimly-lit rehearsal room. I noticed more than a dozen people in the room at the time. I thought to myself, probably due to lack of confidence at that time in my life, “Hell, I’m not going to get this.” Then I started witnessing and hearing some of the so-called Beatle sound-alikes. I decided, “I think I got a shot here.”

I walked up to the music director, Sandy Yaguda. Interestingly, I found out that he had been one of the background singers for Jay and the Americans. Sandy had a good relationship with Steve Leber, part of the successful management team known as Leber and Krebs. At that time, they were managing the successful group Aerosmith.

Upon talking to Sandy with regard to what this was all about, he told me it was a show developed from a small stage show somewhere in Texas. The show had been brought to Leber and Krebs by the somewhat-famous lighting designer Jules Fisher. Sandy said, “The goal is to bring the show to the Winter Garden Theatre on Broadway in New York.” The time frame was such that Beatlemania would be next in line after Fiddler on the Roof closed. I said, “Sounds like fun,” and asked what songs were planned for the show. Sandy had a list of about 50 tentative songs. He showed it to me and asked, “Are you familiar with Beatle songs? You have a youthful look and could be perfect for the McCartney role.” I said, “That’s precisely what I’m here for. I’m a big Beatles fan.” Looking at the list, Sandy asked, “How many of these Beatle songs do you know?” I rephrased his question, “I’ll give you a buck for every song I don’t know.” In true New York fashion, he said, “Kid, get your ass up there, and show me what you can do.” I looked at him, smiled, and walked up to a grand piano on the stage. I thought to myself, “Let’s put this in high gear and really give him some McCartney.” I proceeded to belt out Maybe I’m Amazed in true McCartney fashion.

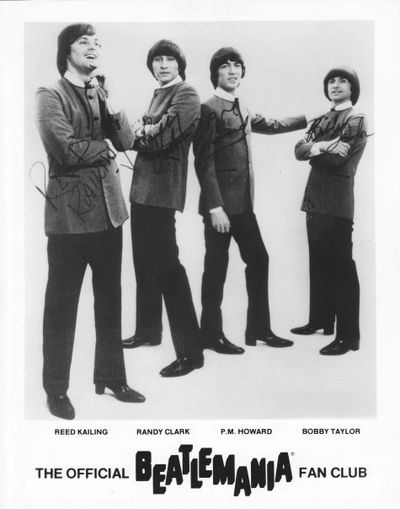

Upon completion, the whole room burst out in applause. Nobody else had received any applause. I glanced over to Mr. Yaguda, who was pacing back and forth at a very nervous pace. I knew what he was thinking. Patty was right, I nailed it. There were voices in the gathering calling out for more. Some contenders actually walked out the door. Without any further hesitation, I proceeded to perform Long And Winding Road. Then went on to do Let It Be. After that, Sandy said, “That’s enough. Fine. We’ve got to talk.” As I left the stage, two guys approached me. One of them was named Randy Clark. He had a striking likeness to John Lennon, but was much taller. He was auditioning for the Lennon role. The other guy, Bobby Taylor, was trying out for the Ringo part. One said, “Man, you just nailed it. Hopefully we’ll get to work together.” The other agreed, “You know what, man? I know you’re in.”

ALL ABOUT ME 45

Reed and Broadway Beatlemania (3)

It must have been the following day that I met with Sandy Yaguda at the Continental Hyatt Hotel on Sunset Boulevard, affectionately known as the Continental Riot House, where all the rock stars were known for heavy-duty partying and destruction of hotel rooms. Sandy and I met on the rooftop. Within moments, I learned that he had already called the producers, Leber & Krebs, and had indicated that he had discovered the Paul McCartney character. He deemed me to be a reasonable look-alike, but a major sound-alike as an alternate McCartney for the Broadway show.

ALL ABOUT ME 46

Reed and Broadway Beatlemania (4)

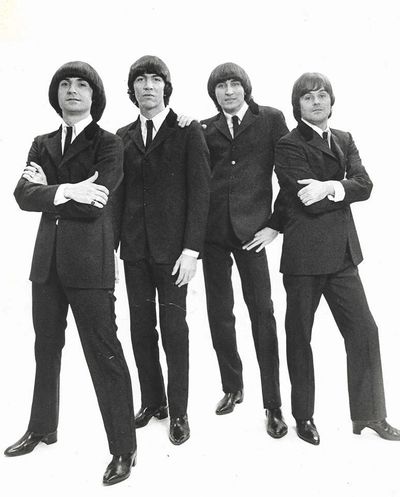

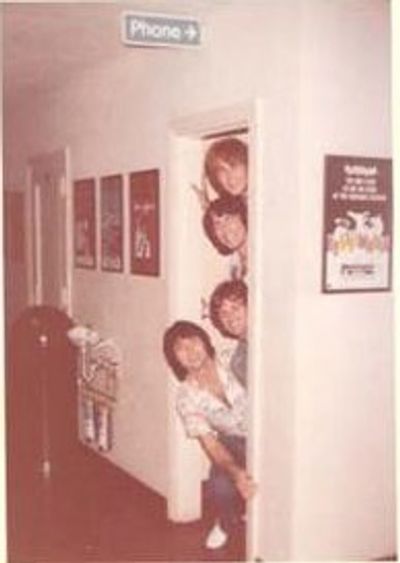

At that time, I was living in the home of a Dr. Gene Carson. The next thing I knew, I had purchased a one-way ticket to New York with Bobby and Randy, whom I had met at SIR during the auditions. We ended up in New York on the redeye flight. Being half asleep, we approached the cab stand. I instructed the driver to take us to the San Carlos Hotel. Well, to make a long story short, we had about a two-hour cab ride. The route this driver took had quadrupled the price of what that cab ride should have cost. Upon turning in our travel receipts to the management company, the lady looked at the receipt and asked, “Did you take a scenic tour of all New York?” My response was, “I really don’t know; I was sound asleep in the back seat.” We checked in the San Carlos Hotel, which was basically a weekly or daily rental facility. It was shared by Randy Clark, Bobby Taylor and some George Harrison guy they found in San Francisco, who lasted only a couple weeks because of an attitude problem, and myself. The stay was neither comfortable nor glamorous. The Harrison character was replaced with a guy named P.M. Howard. I don’t believe he stayed at the same place we did.

ALL ABOUT ME 47

Reed and Broadway Beatlemania (5)

There was a New York cast that had been rehearsing for eight to nine months prior to our arrival in New York. Our first meeting was at New York’s SIR. There we met the New York cast. The Lennon character was Joe Pecorino. The McCartney character was Mitch Weissman. The Harrison character was named Leslie Fradkin. The Ringo character was Justin McNeill. I also met some great off-stage musicians as rehearsals progressed. One was Andrew Dorfman, who played keyboards and wrote arrangements. My favorite was Larry Davidson, who played trumpet and piccolo. Larry was incredible. He was one of the few trumpet players who could actually play the piccolo trumpet part in Penny Lane. To this day, I would like to meet him again. A great lady, Sally Rosoff, was the cello player. Still another wonderful musician, Mort Silver Woodlands, played sax. Peter VanWater played violin. I really enjoyed Peter. He was so supportive when I had to perform Helter Skelter live. You see, if the tape broke down, the stage manager would look at me and point his finger from off stage to perform it live. I sang it in the original key of E, with no disrespect to Mitch who performed it in the key of D. Peter would run to the side of the stage to hear my live performance.

ALL ABOUT ME 48

Reed and Broadway Beatlemania (6)

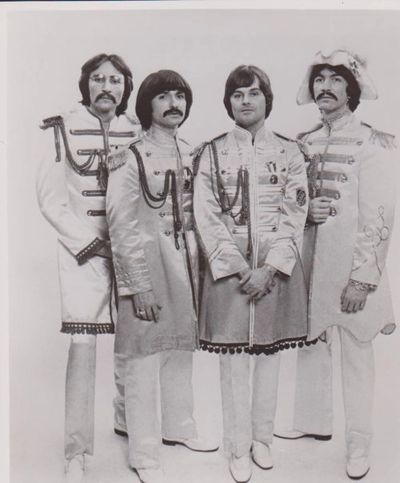

We began rehearsals with the Harrison character from New York, and everything was moving along at a reasonably good pace, considering that--as previously mentioned--the originally-cast Harrison character with the attitude problem was replaced. Once Howard settled in as the new Harrison, things progressed briskly. After rehearsing for a period of time, the date was set to open at the Boston Colonial Theater. The two groups, the New York cast and the Los Angeles cast, were known as Bunk 1 and Bunk 2 respectively. Bunk 1 had already gone forward to have its outfits--pre-Beatles suits and Sergeant Pepper suits--made and readied for performance. The suits were made by New York’s finest, Otto Pearlman. Our suits were not yet completed at this point.

We moved on to Boston, settled in, and began rehearsals. The Bunk 1 or New York cast rehearsed on stage daily. Rehearsals were mainly for the benefit of Mitch (the McCartney character) and Joe (the Lennon character), who were not really highly-trained vocalists. Rehearsal time also consisted of setting up multiple visual screens and scrims, as well as backdrops to project videos and still photos. All this was done to make Beatlemania a true multi-media event.

ALL ABOUT ME 49

Reed and Broadway Beatlemania (7)

On the evening prior to hosting Coca Cola, a major sponsor, both Mitch and Joe had literally blown out their voices from overextending their vocal capacities. This was more the case for Mitch than for Joe; but both were vocally wounded. Sitting in the theater, I flinched during the rehearsal. I could hear Mitch’s voice give out. The band stopped, and everything came to a standstill. Steve Leber walked down the aisle toward the stage and said, “What in hell is going on here.” He reiterated that line at least three times. Behind him was the sound designer, Abe Jacob, who was one of the original designers to bring sound to the Broadway stage. I walked to where they were gathered at the base of the stage and overhead the problem at hand. Yes, both Mitch and Joe had blown out their voices. Leber was perplexed due to the fact he had the show for the Coca Cola folks the very next night, but he had no group.

After some time had passed, I offered a suggestion. I said to Steve Leber, “We can fix this.” And Abe Jacob was all ears. I suggested, “If Abe Jacob can get a Neiman recording-quality microphone backstage for both Randy and myself, plus a camera and visual monitor in the back room, we could sing the songs backstage. Meanwhile, Mitch and Joe would lip-synch on stage. We could see them on stage from the back room.” Leber looked at Abe and asked, “Is this at all possible to do?” Without a doubt, Abe responded, “Yes.”

The next night arrived, and Randy and I sang for Mitch and Joe. I believe, to the best of my knowledge, that the show ran quite successfully. I doubt that anybody knew the difference. Joe made an amazing recovery, where as Mitch still had a severe vocal injury to contend with. I proceeded to perform the next eight shows without Randy, just for Mitch. They were total successes.

Interestingly enough, although the shows were papered (freebies), Coca-Cola pulled out as a sponsor. This was due to the fact that the Come Together song, by John Lennon, contained the line “He shoots Coca-Cola” in the lyrics. Leber scrambled to obtain new sponsorship. To my understanding, at the very beginning, he had acquired his first major backing from CBS Records, which had the group Aerosmith. I believe Leber was able to get an advance to do the show based on the “face value” of Mitch Weisman as a total look-alike for Paul McCartney. Finally our outfits were completed, and the show came to progress at a normal pace.

ALL ABOUT ME 50

Reed and Broadway Beatlemania (8)

As things happened, I replaced Mitch on an ongoing basis. I sensed a touch of stubbornness and jealousy (perhaps not undeserved) on the part of the New York cast. I came to feel that Joe Pecorino did not appreciate allowing the L.A. cast to dominate his stage. On one occasion, I recall not being allowed to leave the Winter Garden Theatre until after intermission. Mitch had returned and appeared capable of completing the show at that point. I remember on another occasion, I was preparing to leave the theatre just before intermission. Mitch was singing the song Yesterday, and his voice started to falter. Bob Strauss, the stage manager, told me, “You better hold off before leaving, it sounds like Mitch is in trouble again.” From Yesterday until the intermission was about 20 minutes, at which point I was told, “Go to the second floor for makeup and get dressed.” I was going on. From that point on, I performed the rest of the show.

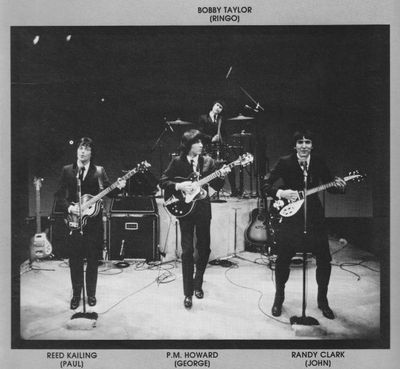

You need to understand that when I went on to perform with the New York cast, I had to sing Mitch’s parts, which were the low George Harrison parts. Joe would sing the Lennon parts, and Leslie would sing the high McCartney parts. On the other hand, when I performed with the L.A. or Bunk 2 cast, I sang the McCartney part, P.M. Howard sang the Harrison part, and Randy Clark sang the Lennon part. You know what? I had to know two roles, and I really got tired of it.

ALL ABOUT ME 51

Reed and Broadway Beatlemania (9)

I was once again asked to fill in for Mitch Weissman. I had a high level of respect for Mitch and his talents; and sometimes vocal breakdowns do happen. But I had my own issues to deal with. I came to be called the “Iron Throat.” Come to think of it, I saved that show from going dark. I simply got tired of it. At that time, I had called a meeting with Joe Pecorino, Leslie Fradkin, and Justin McNeill and said, “Look, if you won’t allow the L.A. cast to go on, but you want me to sub for Mitch, I have no problem with that. But I’m going to sing the McCartney part. Leslie, you’re going to sing the Harrison part. Joe, do what you do.” We all agreed. We went on and did some great work. The problem was that all of this created a lot of animosity with the other members of the L.A. cast.

ALL ABOUT ME 52

Reed and Broadway Beatlemania (10)

The experience of performing on New York’s Broadway stage marked a very memorable transition in my life. I recall the nights I was standing offstage before going on. There was a gentleman there, in a capacity similar to stage manager. His name was Charles. I learned so much from him. And just being a part of Beatlemania was a high point in my life.

I recall that long after I left, there were multiple lawsuits over issues I prefer not to go into here. But at the very beginning, when I was going through all the hardships with Player and had auditioned for Beatlemania, I went to see Bruce and Ronnie Grakel at their home in Brentwood. I asked them what should I do. “Do I perform this show or not?” I had concerns over the sensitivity of all the material being Beatle related. Interestingly, Bruce informed me that he had spoken to Ringo Starr about this same matter. Ringo said, “Tell him to go for it.”

Once Charles, the stage manager, saw me yawn as the prelude to the show was starting. He said me, “Kid, you’re yawning.” I replied, “I’m getting tired.” His response was, “You’ve got one of the best voices I’ve ever heard while managing this stage at the Winter Garden.” Charles being the dapper gentleman he was, I listened to every word he said. There was another alert that maybe it was time for me to become more independent of the show. I had been used a lot. Charles said, “When you start to yawn before going on, you lose your natural energy to perform.” At the moment he mentioned that, I remember Bobby Jones walking up the stairs behind me to our dressing rooms. Like a mantra, I kept repeating, “I’m so tired, I’m so tired.”

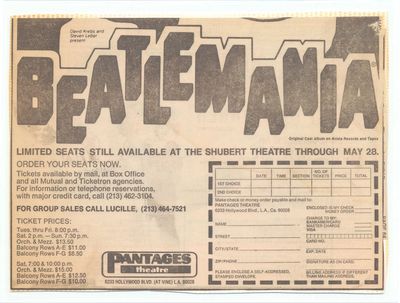

It was shortly thereafter that I contracted mononucleosis. Physically, I was war torn; mentally and emotionally, I had been beaten up. I had been doing the work of many people. I saw a doctor, who prescribed a badly-needed break. On his advice, I went on a six-week hiatus. I returned to Wisconsin for some rest, after which I headed for the Pantagas Theater in Los Angeles.

ALL ABOUT ME 53

Reed and Broadway Beatlemania (11)

The New York cast had previously opened up in Los Angeles at a location in Century City. I had completed my hiatus and was ready to resume my Beatlemania role at the Pantagas Theater. Increasingly, I started to distance myself creatively from Beatlemania and shifted my energy toward writing my own original music. Songs included Rock And Roll Me Over and Point Of No Return, both composed by myself, as well as a number of tunes such as Love Eyes, It’s Over, Twenty-Four Hours, and You, which were co-written by KiKi Dee and myself. Gradually, I came to reinvigorate myself creatively. Beatlemania became a thing of the past; and I, Reed Kailing, once again emerged for the present and future.