ALL ABOUT ME 21

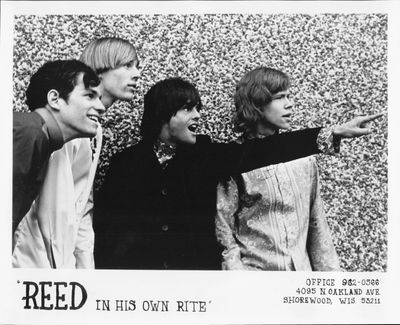

Reed Leaves the Destinations to Form "Reed in His Own Rite"

The person who was replacing me was Gene Deuvanal; he was a member of the somewhat locally-successful band called the Red Coats. Although Gene was an excellent, flashy, agile guitar player, there was one thing that Con Merton and his newly-acquired group had overlooked in their quest for control, power, and money. This error ended up costing them dearly. I had a strong following among fans of the band. Needless to say, the Destinations died a quick death. When the band’s members tried to reclaim their spot on the Swinging Majority show, Art Roberts retorted firmly, “Without Reed, you’re nothing. No Reed, no go.” Art put the band members and Con Merton, who had conspired with Judas to pull off the routine, in a state of total surprise. He then kept Reed as a solo act.

Afterwards, Fred Hadler admitted that going along with Judas and the Con man were the biggest mistakes he had ever made in his life. Still another of the sad points about this whole ordeal involved the Judas character’s brother. The brother of the power player and I were best of friends. The selfish, arrogant behavior on the part of the particular band member damaged my relationship with his brother for many years. Today, he and I have made amends and now realize how silly the whole incident was.

After getting over the shock of the this unfortunate episode of my life, I thought the best thing to do was to maintain a healthy attitude. I felt the need to forgive, forget, and move on. I went to the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM) campus dance that we used to play in order to show my support for the band in the hope that we could maintain some form of friendship. I had already begun plans for my next venture, "Reed In His Own Rite," and felt that it was time for everybody to move forward. Unintentionally, I created quite a stir with the audience. I found that I had some very loyal fans. But the aftermath of my well-intentioned effort was finding out that the band thought I was there to sabotage their show and distract the audience’s attention away from the performance. After displaying such a negative attitude and immature behavior, it was no surprise to me to see that the band was very short-lived after that point.

I took a brief time out after the Destinations; then I progressed with Reed In His Own Rite. At this time, we did some adventurous things, like working with Mahalia Jackson, the world-famous gospel singer. I had been taken under her wing in a project called “Give a damn.” This was a program she was spearheading that tried to ease the tensions between whites and people of color. We did a show in Chicago with a blockbuster variety of stars, including Jimmy Durante, Dinah Shore, Della Reese, Jerry Butler, Robert Culp, and Mahalia herself. It was truly inspiring to work with entertainers of that caliber. I gave a speech during that performance, right after the song I love you by the People. My talk received a huge round of applause. Many dignitaries were present, including the governor and columnist Irv Kupcinet, who came back stage and praised my presentation.

Yes, Reed In His Own Rite had been born. I started working on my new musical venture with Bruce Robinson, Tom Stewart on drums, and a keyboard player whose name I can’t recall. The band performed diverse styles of music like Cream, Beatles, and other popular songs of the time period. The band moved forward, acquiring a new Hammond B3 keyboard player by the name of Rick Shear. We acquired a home on Downer Avenue in Shorewood, which was actually my grandparents’ winter home. The band was explosive, very tight, and fun to play in. The members of the band–Bruce Robinson, Tom Stewart, Rick Shear, Dick Keskey, and myself–all shared that house together. The arrangement started to work out well, until unfortunately several of the band members ran into serious problems with drugs. A couple of the guys–not I myself--heavily got themselves into the really-nasty stuff. I got scared because the Shorewood police were cruising past the house. My father, you see, had given us the house free of charge, and I felt responsible for what was occurring. It really started to wear on me. At one point, my father said, “Reed we’ve got a problem.” My father and I confronted the two members about our concerns, and of course they remained in total denial. We threatened to shut down the whole operation unless they got clean. The band deteriorated, and tensions escalated to such a degree that while we were performing somewhere in Illinois, one of the members got up and walked off the stage. We went on as a three-piece band and carried on as such for a period of time. That arrangement was short lived.

ALL ABOUT ME 22

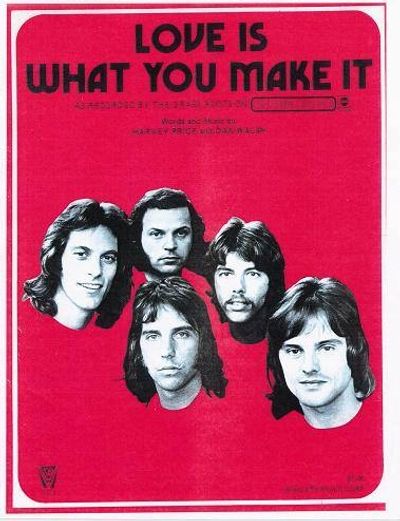

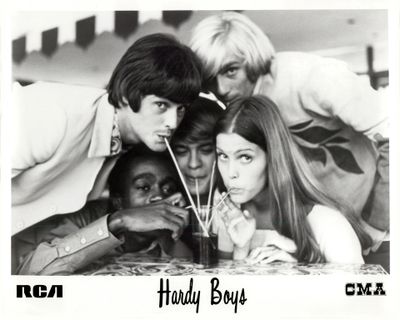

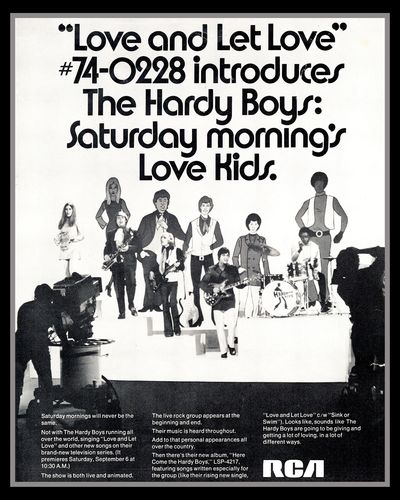

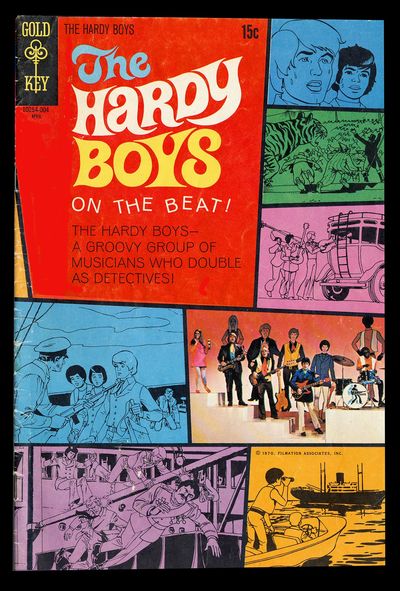

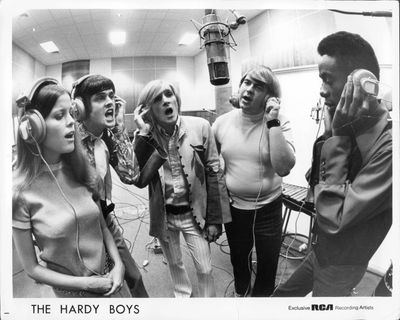

Reed and the Hardy Boys

My life began to change once again as a result of performing as a solo act on Art Robert’s Swinging Majority show. I had been observed by the folks at Filmation, an animation company, much like Hanabarbara of the Flintstones fame. I was contacted by Norm Prescott and Lou Scheimer of Filmation to be a part of a show called The Hardy Boys, based on the short stories of the best-selling author F.W. Dixon. At that time, Jim Golden and Bill Traut of Dunwich Productions were involved. Their responsibility was to produce the music for the animated show for RCA Records. Interestingly, the engineer who worked with Bill and Jim on these recordings was Brian Christenson. Brian had been the one who worked on the Hello Girl demo that we recorded for Art’s show at Navy Pier.

ALL ABOUT ME 23

Reed and the Hardy Boys (2)

I recorded the demo Feels So Good, written by Gary Loizzo of the American Breed. This demo was recorded to convince Filmation to select our band from the groups then under consideration. That recording won us the audition, and the audition got us the job. I was to play the role of Frank Hardy. I had suggested that I knew somebody who could fill the character of Joe Hardy. His name was Jeff Taylor, from the Milwaukee band known as The Messengers. It’s interesting to note that Jeff’s voice can be heard on the version of Midnight Hour performed by Michael and the Messengers, on which I sang the background vocals. Midnight Hour was recorded on the USA label, which was the sister label to Destination records. The others members of the Hardy Boys gang were found by Dunwich Productions. Devon English was the Wanda Kay character, Bob Crowder was the drummer, and the sax player was Nibs (Norbert) Soltysiak. Using a variety of studio musicians selected by Dunwich Productions, we recorded two albums for the ABC TV show at RCA Records on Wacker Drive. It was a fun time. While at the studio, I also had the opportunity to meet Burton Cummings of the Guess Who.

ALL ABOUT ME 24

Reed and the Hardy Boys (3)

The opening of the show was depicted as playing a live concert, performed at Second City on Wells Street. The show debuted on a Saturday morning and was shown in 52 different markets. Prior to the opening Saturday morning show, there was a huge party given in our honor at the Cheetah in New York. There was also a press junket for people in the media, which attracted reporters from many newspapers nationwide as well as representatives from several popular magazines. The show became a hit series for ABC with the Saturday morning audience. The single Love and Let Love and the following two albums were moderate successes. Interestingly, my version of Hello Girl was used on one of the shows. The music was integrated right into the show and appeared to be performed by the cartoon characters themselves. Filmation had high hopes that Hardy Boys would become a commercially-viable live band and embellish the organization’s wealth. Filmation had done so successfully on a previous TV series, called the Archies, with the band’s hit single Sugar Sugar.

ALL ABOUT ME 25

Reed and the Hardy Boys (4)

The group did play some live shows, such as a Junior Miss Pageant in Birmingham, Alabama. We decided to drive the band down. By the time we reached Nashville along the way, we stopped to get something to eat. Two restaurants refused us service because we had a Black drummer. We finally arranged to get something to eat at a small outdoor hotdog stand located on a college campus. We proceeded to Birmingham, where we had reservations at the Putweller Hotel. Upon arriving, we were escorted to the second floor, where musicians and people of color were segregated. I clearly remember we were there for a two-day stay for rehearsals. The first evening after rehearsal, Jeff and I went to the hotel lounge to watch Steppinfetchit, who was a well-known Black comedian, much like Red Fox. Steppinfetchit was also staying on the second floor.

ALL ABOUT ME 26

Reed and the Hardy Boys (5)

I came to realize that I no longer enjoyed performing with the Hardy Boys. The band was mediocre at best. It certainly did not display the caliber of musicianship that I had become accustomed to working with. I was locked into a two-year contract with Filmation, and at that point, I was nearing the end of the first year. Both albums had been completed, and there really wasn’t much left to do. I seriously entertained the thought of leaving the show.

At this time, I was going with a lovely lady by the name of Patty Potter, whom I would later marry. Today, Patty is remarried to a wonderful gentleman named Hal Bosworth. She and her husband are among my dearest best friends. To this day, they have a wonderful marriage and have a beautiful daughter, actress Kate Bosworth. Patty and I talk quite often.

ALL ABOUT ME 27

Reed and the Hardy Boys (6)

I talked to Patty about leaving the Hardy Boys, and she concurred that perhaps there were better avenues for me to take in the entertainment business. Unbeknown to me, because of the shoddy attorney that I had used to put the deal together, he neglected to tell me that if I elected to leave without being legally released by Filmation and Dunwich Productions, I would have difficulty pursuing other ventures in the entertainment industry. So my career once again temporarily came to a sobering halt.

Due to the fact that Patty and I were engaged to be married soon, I realized that I needed a job. I proceeded to search and landed a job at Allen Winston’s, on Oak Street, the same store where I bought all my expensive clothes while with the Hardy Boys. There I sold clothes. I really looked the part. I dressed well and wore the same clothes I had bought at the shop while working there. That job lasted a couple of months. I became very frustrated. There was not a lot of money or satisfaction coming out of doing that kind of work.

ALL ABOUT ME 28

Reed Learns the Music Business at MCA Distribution

I talked to Paul Christy, who was a good friend of mine. Paul was Program Director at WCFL radio, the "Voice of Labor" in Chicago. Paul suggested a job in the record distribution business. It wasn’t a lot of money, but the education proved to be very valuable. Paul gave me the name of a Tony Ignofo, who was the District Manager for MCA Distribution in Skokie, Illinois. From where I was living on Sheridan Avenue in Belmont Harbor, it required an hour and fifteen minutes to get to work. I would get up at 5:00 a.m., take the “L” and then a bus, punch the clock, and then start in the back room picking orders for the rack jobbers at $85 per week.

MCA covered eight different sub-labels, among them were Universal and Decca, as well as others. Paul Christy was an interesting guy. As I mentioned earlier, Michael and the Messengers had been produced by Paul. Paul and I worked together extensively on other recording projects as well. He and his wife, Joanie, one of the sweetest ladies in the world, were Patty’s and my own closest friends and remained very loyal.

Needless to say, working in the back room were some interesting characters. The one who stood out most in my mind was a cool Black gentleman, who went by the name “Bulldog.” He was the packer; he packed up the orders. One day, Bulldog showed up for work, greeted us with his usual “Good morning everybody” and wave of the hand. But this time when Bulldog held up his hand, we saw light shining through. Bulldog had been caught with a girlfriend. His wife, a rather colorful lady, asked him which hand was used to touch his girlfriend. Then the wife shot a big hole through his right hand. Having received medical attention for the incident the previous night, Bulldog was both proud of it and out if it. He showed off his unbandaged, blood-stained wound. There was never a boring day working in the back room.

ALL ABOUT ME 29

Reed Learns the Music Business at MCA Distribution (2)

There were some high points on the job as well. Elton John, on his first concert tour during which he opened for Eric Clapton, visited the distributorship. His real intention, being an avid record collector, was to fill three empty suitcases that he brought along with records by Patsy Cline and various historical artists.

I also recall when Rick Nelson’s Stone Canyon Band performed at Mr. Kelly’s on Rush Street. Patty and I attended the show. It was a week-long engagement. Surprisingly during that week’s time, Rick who recorded on the MCA label, never stopped in at the MCA distributorship. While Rick was performing in Chicago at Mr. Kelly’s, the order pickers retaliated by intentionally mispicking his albums for shipment to record stores. What I knew, but the warehouse people did not realize, was the fact that Rick Nelson had a crippling shyness problem. He wasn’t a visitor, he just didn’t like to go out or hangout with other people. Unfortunately, people simply misread him.

As time passed, my life began to take another turn. Patty and I briefly traveled to Los Angeles, where we got married on October 10th,1970 in La Canada. We enjoyed a brief honeymoon in San Francisco, and then returned to Chicago. Upon returning, we realized that remaining in Chicago was not in the cards for us. Patty and I preferred the California atmosphere and lifestyle.

It became rumored among my colleagues at the distributorship that I had connections with Paul Christy of WCFL radio. This buzz proved to be a valuable asset. Herb Chapman, the ordering manager for all eight MCA labels, was at the brink of retirement. I was promoted to replace Herb in that position. I was now in charge of ordering for all eight labels under the MCA umbrella. I was responsible for pulling the ordering cards and overseeing the inventory.

There was a Bob Dylan or George Harrison tune (I forget which) that Olivia Newton John had performed called If Not For You. I got it played on WCFL radio. I showed up for work and found green cash in my desk drawer. I took my drawer full of money and turned it in. I walked into Tony Ignofo’s office, and he said, “Pally;” he used to call me Pally. “Pally, what can I do for you?” I told him, “You can take this back.” He said, “What are you talking about? I don’t see anything.” I replied, “I don’t think this is going to work for me.” I was concerned about Paul’s reputation, and accepting payola was illegal.

Having dinner at Paul’s house sparked a conversation about an album that had come out, entitled Jesus Christ Superstar. I mentioned to Paul there was a song that was an incredibly striking single that neither the MCA label nor the record promoter at the distributorship was pushing. I asked Paul to give it a listen. Paul called me the next day to tell me that I was right. He agreed that the tune was an incredibly strong single. As people in the industry knew back then, every album needed the help of one, two, or possibly three songs off the album as singles to be calling cards for that particular album and promote its longevity. Tom indicated that he would plug the single between 12:00 midnight and 6:00 a.m., and then wait see what happened after that.

Paul told me, “You’re the ordering manager now. What you’ve got to do is cover your butt, get the feed from all the different rack jobbers in the field, and order sufficient quantities to get stock to the stores. If you don’t have the product in the warehouse, you can’t get it to the stores, and it doesn’t sell.” Paul continued, “Don’t say anything to anybody. Order 50,000 albums. You’re breaking the single, and this album’s going to be big.” I said, “Oh, my God! 50,000 albums, forget it.” Reluctantly, I called Pinkneville, Illinois (the mothership or the main supplier) without telling Tony anything about it, and put the order in. The next day, 25,000 albums showed up on our loading dock. The loading dock manager went to Tony’s office and said, “My God, we got 25,000 in and another 25,000 on back order. I returned from lunch to find chaos. I found an absolutely-crazed, out-of-control manager. He had gone ballistic. I could hear him yelling from the front office to the very back of the shipping room, which was approximately 60 yards long. I asked one of the secretaries who had a stern look on her face, “What’s the problem with Tony? What’s gone wrong now?” She said, “Ah, it looks like you're in deep sh_t.” I replied, “Oh, really.” I walked through the swinging doors and saw Tony approaching as if to kill me. He was red in the face and already had a heart condition; I was scared to death he was going to drop dead right then and there. He yelled at me, “Pally, what in hell do you think you are you doing here? We got 25,000 albums sitting on our loading dock, and you’re going to eat every damn one of them.” I said, “Tony, relax. I got this under control. Believe me.” Within just 48 hours, three-quarters of that order were gone. Tony came to my desk and inquired nervously, “Pally, when are the remaining 25,000 coming in? We’ve got a blockbuster on our hands. Good for you, kid.” I was a hero, and Tony looked like a genius to the people in the regional office located in Detroit.

But for every good turn, something else gets ugly. The in-house record promoter, Lenny, who got his job from two exceptionally-powerful independent record promoters, looked stupid. MCA’s own in-house record promoter had mud on his face. He didn’t get the job done that he was being paid for. I, on the other hand, looked brilliant. I was the one responsible for getting the record played and generating astronomical sales figures. I can still see the look on Lenny’s face as he stared me down through the glass window of his office, as if to say, “I’m going to get you. Yes, I’m going to get you.” I could see it. I felt it.

Paul was fired from WCFL. It was rumored that as he arrived at the station, warning shots were fired at him. He assumed it was the sound of gunshots ricocheting about 20 to 30 feet around him. When he got in, he realized his gig was up. He had gotten the message. There were never any hard feelings between us. We remained friends for many years. And it was at that time I made up my mind to move on.

ALL ABOUT ME 30

Reed on the West Coast

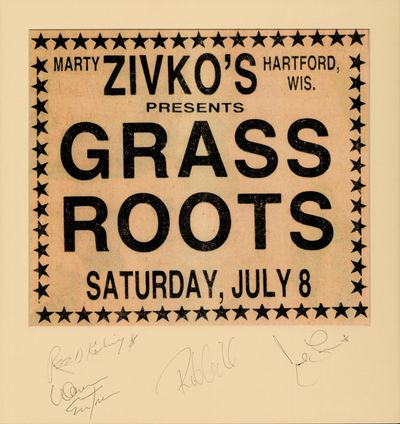

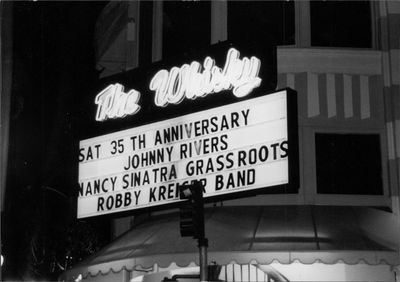

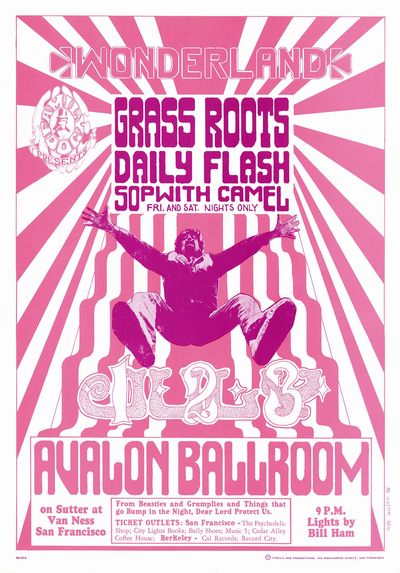

I called my friend, Fred Bohlander, who headed up International Creative Management (ICM), a popular booking agency located on Beverly Boulevard. He and his partner, Danny Weiner, would eventually form their own extremely-successful booking company, Monterrey Peninsula Artists, located to this day in Monterey, California. Fred, who was involved with Dunwich Productions at the time that I was doing the Hardy Boys, and I became very good friends. I asked Fred, “If you were me, and knowing what I’ve gone through, would you go to the West Coast, or would you go to the East Coast.” His reply to me was, “Who do you know on the East Coast?” I said, “Not too many people, certainly nobody of any substance.” He answered, “Well, at least you know me. Why don’t you and Patty head west?” Patty and I talked it over. We made the decision to move to California in the latter part of 1970. We resided with her parents until we were able to get our first penthouse apartment in West Hollywood several months later. Patty landed a job with Robert Ellis and Associates, a public relations firm. One of its several clients was Diana Ross, who Bob married. The other key account, most important to me, was the group called the Grass Roots.

I started an ambitious campaign. I took the demo songs that I had recorded previously in Chicago with Paul Christy and made the usual rounds to various music publishers and record labels. Bill Trout of Dunwich Productions (i.e., Hardy Boys) was kind enough to share a list with me. I soon came to realize just how difficult the task ahead of me was going to be, and I became increasingly discouraged with the passage of every day.

ALL ABOUT ME 31

Reed on the West Coast (2)

Finally, Patty came up with an absolutely brilliant idea. One morning, she took my tapes to work and gave them to Bob. Patty wanted to see what he thought and what connections he might be able to utilize. Bob was a great guy, but was very cautious about matters of this nature. First, he didn’t know me very well. Second, he had started out on his own and didn’t really know that much about music himself. Bob felt sort of handicapped in this regard; hence, he preferred to move cautiously. Third, Bob was particularly careful because his wife was Diana Ross.

Bob played the tape at home, where Diana lived. The incredibly modern home, which was owned by Max Factor, was located on Maple Drive in Beverly Hills. Diana happened to overhear the recording as it played and inquired who the artist was. Bob said it was the husband of the lady who worked for him, and he had been asked to give it a listen and see what he might be able to do. The song that Bob liked most was entitled Claudette Mauden, a tune that I had written after having been inspired by the Beatles’ Let It Be.

Diana was a very private person and engaged in her solo career. To my surprise, I was invited to meet with her and Bob at the MoWest Offices on Sunset Blvd. MoWest was a subsidiary of Motown Records on the West Coast. I met with Diana on a late Saturday morning. She was formal, yet incredibly engaging, and a very beautiful woman. Everything was going well until I happened to mention that Bob had dropped me off. Apparently, that was the wrong thing to say. Bob, you see, had told her a different story concerning where he was going to be at that time; and there went my career with MoWest. I quickly discovered that I really had to watch what was said in negotiations.

The West Coast had taught me an important lesson. In situations like that one, I needed to stick with my original intent and never waver. I, unfortunately, learned the hard way.

ALL ABOUT ME 32

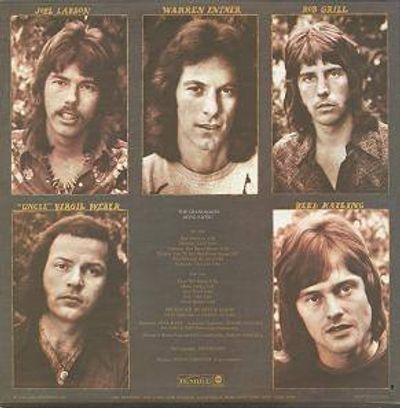

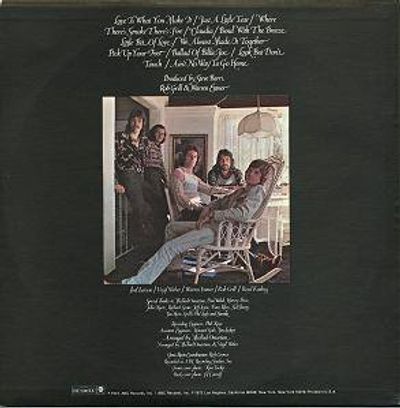

Reed Joins the Grass Roots

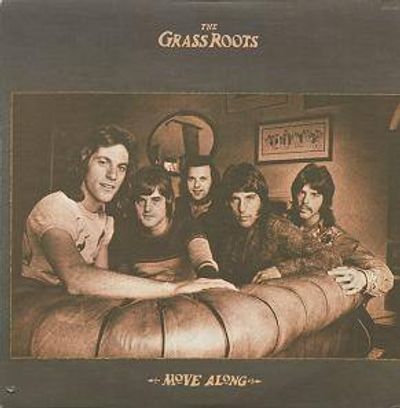

Somehow, Bob managed to make the best out of an otherwise bad situation. Representing the Grass Roots, Bob decided to give the tape to Warren Entner, who in turn liked the tape a lot. In a strange twist of fate, Patty and I were planning to move into the penthouse apartment just across the street from Warren. I recall meeting with Warren at his house on Miller Drive above Sunset Boulevard. The home had originally been owned by F. Scott Fitzgerald. The photo on the cover of the Move Along album, on which I recorded, was shot in the living room. Coincidentally, Patty’s and my apartment had once been inhabited by Fitzgerald’s mistress, Zelda. Rick Coonce happened to stop by and also heard the tape. He commented, “This stuff is great. Why can’t you get a record deal? ” Warren replied, “That’s precisely what I’m going to try to accomplish with Reed.”

Time passed without results. “We pass,” were the first words on the lips of the people we approached. Warren Entner and I had bonded musically. It was at about this same time that a guy named Terry (not Terry Furlong) was thinking of leaving the Grass Roots. The other members seemed to concur that the time had come for both the band and Terry to go their separate ways.

ALL ABOUT ME 33

Reed Joins the Grass Roots (2)

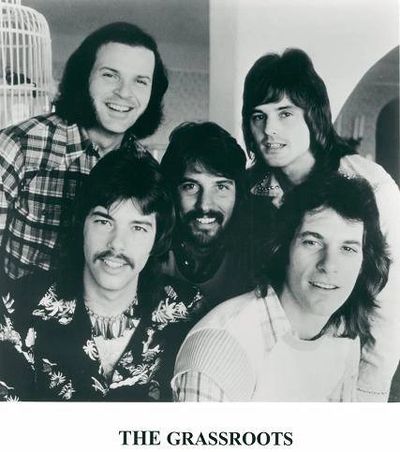

Rosemarie, Warren’s wife, planted a seed. She asked Warren, “Why not replace Terry with Reed?” As things turned out, I became a member of the Grass Roots. Things worked out very smoothly, and I felt comfortable and relaxed playing with my new colleagues. The first time that I met Rob Grill, other than merely in passing at Art Roberts’ show, Rob appeared a bit suspicious of me. Initially, he resisted change. Upon meeting at Warren’s house on a Saturday afternoon, we exchanged pleasantries and got right down to the business of ascertaining whether we could sing together compatibly. On a scale of one to ten, we hit eleven. We sang Where Were You When I Needed You, Midnight Confessions, and their current single at the time, Glory Bound. After we finished, an incredulous Rob Grill looked at me and asked, “How do you know these songs so well? They sound great, as if you had been performing with us for years.” I replied, “Actually, I have been performing these songs for years. Where Were You When I Needed You was one of my all-time favorite songs. My high school band covered it.” He got a little bit disgruntled in a jocular way and commented, “Gee, are we that old, or are you that young?” It was all in good humor.

ALL ABOUT ME 34

Reed Joins the Grass Roots (2)

My first gig with the Grass Roots was performed with minimal rehearsal. I simply got a call from Warren. He said, “We’re opening up for Three Dog Night this weekend in South Bend, Indiana.” I said, “Wow!” The band members at the time consisted of Dennis Provisor, Joe Pollard, Rob Grill, Warren Entner, and myself. The show was paralyzing. Unfortunately, I learned that Dennis and Joe were planning on leaving the band. This upset me. Joe was an incredible musician. Dennis, an incredible singer and songwriter, was pursuing a solo career. Later that night, we partied until dawn. Danny Hutton of Three Dog Night educated me about the realities of a rock and roll lifestyle. I remember lying in bed the following morning, waiting to be called to get to the airport and thinking, “I just played with my all time favorite band.”

Upon returning to Los Angeles, the reality set in that Dennis and Joe were indeed leaving, and we had to refashion the band. I had a talk with Warren at his house, and I remember telling him, “This is not my band.” This was going to be a vulnerable time for the band, since Dennis was so well woven into the fabric of the band. We weren’t just changing personnel; we could end up changing a sound. Dennis provided an incredibly soulful sound. Warren had mentioned that Steve Barri had found a keyboard player by the name of Virgil Weber. Virgil had been traveling with the band called Climax (the group that performed Precious and Few), and I knew what the guy was all about.

ALL ABOUT ME 35

Reed Joins the Grass Roots (3)

We had two dates coming up the following weekend, during which time Ricky Coonce performed with the band. Rick was one of the greatest guys you would ever want to know and have as a friend, but there was a problem. Rick had absolutely no sense of time and rhythm when it came to drumming. Upon our return from the gig, I informed Warren, “If he stays, then I’m leaving.” I believe Rick Coonce now lives in Vancouver, Canada and is employed as a social worker.

I recall Warren asking, “Who are we going to replace him with and still keep our costs in line?” I had befriended a guy by the name of Joel Larson. His girlfriend, Janice, made incredible ribbon outfits and purses. Joel had been part of the original Grass Roots from the San Francisco area, that had a hit record called Mr. Jones. From what I understand, the band was then invited down to Los Angeles and, to my understanding, recorded a P.F. Sloan and Steve Barri song called Where Were You When I Needed You. Again to my understanding, after having recorded the song, one or another of the band’s members--other than Joel--fell victims of the drug world. The group had disbanded. Henceforth, Warren Entner, Rob Grill, Rick Coonce, and Creed Bratton constituted the reformulated Grass Roots in 1967. Now, going back to the reformation of the Grass Roots, I asked Warren, “Since Joel Larson was the band’s original drummer, and due to the fact we had so little rehearsal time, why not use Joel as a drummer? Warren mentioned the idea to Rob Grill, and there was a big to-do about Joel. Apparently, there were some unfinished business matters pertaining to Joel that left a bad taste in Rob’s mouth. Nevertheless, eventually the disagreements were worked out, and Joel once again became a member. The band had been now reformed.

ALL ABOUT ME 36

Reed Joins the Grass Roots (4)

The Grass Roots performed in many and diverse venues, including a performance to be aired on the innovative ABC show, David Sontag’s In Concert, and Wolfman Jack’s Midnight Special on NBC. A true highlight in my career was performing two shows, on Friday and Saturday nights, with the Nashville Symphony Orchestra. Just imagine the thrill of performing Grass Roots songs backed by an 87-piece world-class orchestra. A magnificent harpist played directly behind me. I heard heavenly glissandos that I never heard before or since. The conductor had completed the orchestral charts just a couple days before the actual performance. The charts arrived in the luggage of the conductor, who flew in the day before the rehearsal. The rehearsal was a white knuckle flight. We had only a single run-through. But after all was said and done, both shows came off flawlessly. I had many wonderful, exciting times while performing for the Grass Roots. To this day, I thank Warren Entner for letting me tag along, and I consider him a good friend. I deeply appreciate his support at those times when I really needed it.