COMPLETE BIOGRAPHY: ALL ABOUT ME 1

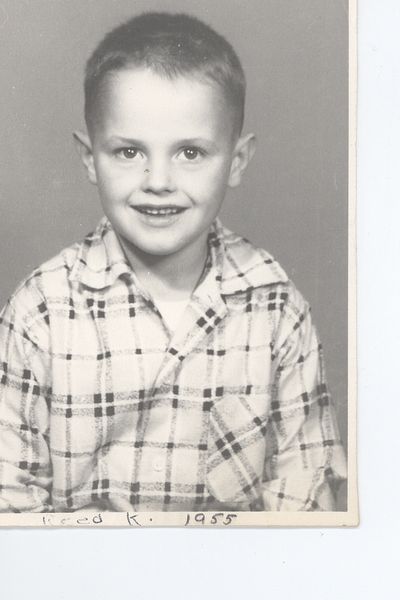

In the Beginning ... Reed in Waterford, WI

It was on a hot, summer day in Waterford Wisconsin, 1956, that my friend Jim Scarry bumped into me and asked, “Have you heard about Elvis?”

“Who’s that?” I replied.

“Elvis Presley just released Hound Dog. This is hot; it’s gonna be big!” Jim said.

Unknowingly, Jim had planted the seed. I was 9 years old at the time. Nothing much was happening as I spent my days sitting by the banks of the Fox River bank, catching sunfish, and hearing the bells from St. Thomas Church ring out the passage of every hour. And the nuns at St. Thomas failed to realize how well the sound of voices can travel across water. From time to time, I would eavesdrop on their conversations as they chatted on their private patio.

Yes, it was truly a Huckleberry Finn lifestyle that I was living. Halbeck’s chicken farm, with a huge field, was close to my house. I, the “Little Warrior,” as my mother sometimes referred to me, recall making miniature bows and arrows. I even crafted my own homemade feathers. The self-styled feathers were carefully clipped and painted on the cardboard backings from men’s shirts that my family had sent to Adelman’s dry cleaning establishment. Then, I would terrorize the dirt road that tractors used in order to cross the field. Late one afternoon, a huge bird flew overhead. I recall that, at the time, I felt so small. I yelled to the bird and shot an arrow, missing him of course. “You’ve challenged me; come fight me.”

It was a frustrating time in my young life. Ongoing tension between my parents interfered with performing well in school. And then there was my teacher at St. Thomas School, a stern nun cloaked in black medieval robes. Somehow she maintained absolute control in a hot, overcrowded classroom of 65 kids, during those days long before the comfort of air conditioning. Discipline was maintained at all times with strict punitive policies. I think that even Father Hurdle was afraid of her. I certainly was. She really scared me. I recall having to raise a finger in order to go to bathroom. One time she refused and really embarrassed one of my classmates. After that, I was more afraid of her than ever. I crawled even more deeply into my shell. Afraid to go to school, I constantly stared out the window and dreamed about escaping from my trap. The thought of Huck Finn caught in a cage was an ugly thing for a free bird.

My grandfather on my mother’s side of the family was Dr. Francis Malone. He proved to be a role model for my life. Dr. Malone conducted his medical practice from a home with a beautiful garden in Waterford, Wisconsin. Grandpa had a guitar that he used as a sort of placebo treatment with certain patients. I recall that my grandfather would ask my mother, “Mary, would you like to go out on a call with me? We’re going over to see the Webers.” They would get into a horse-drawn buggy together. He would bring along his guitar and medicine bag. In that bag was a bottle of Irish whiskey. Grandfather had keen insight and knew how to gauge people in the local community. Arriving at the homes of his patients, he could discern those who really needed medical attention from those who just needed support and a dose of good cheer. Depending on the patient, grandfather had an remarkable talent for knowing when and how to calm the soul and sooth a patient’s mind by strumming some Irish ballads, tossing out some old-fashioned Irish humor, and sharing a sip or two of fine whiskey. Some of his patients, many of whom were hard-working farmers with a lonely heart, could not afford the price of a house call; yet grandpa took great pleasure in treating them anyway. Sometimes, he would accept turkeys or other fowl as payment. Grandfather had his own unique style of attending to people’s needs; and to him, it didn’t matter if they couldn’t pay.

Grandfather passed away in 1952, having suffered a stroke about a year prior to his death. He died quite affluent, never having denied anybody medical care. I can still recall the bells of St. Thomas tolling out the noon hour just as he passed. Mealy Funeral home attended to the necessary preparations, but grandpa had a genuine old-fashioned Irish wake in his home. Imagine this: I was a five-year old kid staying at my grandmother’s house, where the wake was being held. Coming down stairs in the middle of the night, I recall seeing a huge parlor portrait of the Madonna and Child. To the right was the casket. Two little fans on tripods blew fresh air on the casket. I, just a naive child at the time, thought I saw him breathe. As if saying a prayer, I whispered as I grasped his lifeless hand, “Grandfather, I’ll always need your help.” Grandfather was well liked by the entire community; and to this very day, a pillar on the property still says Dr. Francis Malone.

In all respects, growing up in Waterford was a wonderful experience. At that time, one of the major influences on me musically was paying a quarter for admission into the Ford Theater on Friday nights for my time of escape. In particular, one film that stands out in my mind is a movie called The King and I, starring Yul Brynner and Debrorah Kerr. The music of Rodgers and Hammerstein moved me to such an extent that, over the duration of time the show played in Waterford, I would pay the 25 cents admission price to watch the film. Then between showings, I would hide under my seat just to catch the second performance.

I was a lonely, introspective kid; you might say I was sort of a dreamer. My two brothers were eight and six years ahead of me. We interacted as much as possible, considering the differences in our ages. My parents planned to move to Shorewood. The prospects of having an opportunity to explore new horizons excited me, and I looked forward to the move. Yet for me, relocating was complicated by discrepancies in the standards between the rural and city school systems. The reality of this intensified my educational struggle. My parents were advised to let me repeat the third grade in a Waterford public school, in order to be brought up to grade level.

ALL ABOUT ME 2

Reed's Early Years in Shorewood, WI

In 1957, the year that the Braves won the World Series, we moved to Shorewood, 4437 North Murray Avenue. The move marked a pivotal point in my life. I really looked forward to the change. It represented an opportunity for me to explore new horizons and to meet and interact with more people, this time in a city environment. My new school was St. Robert’s, which proved to be very different from St. Thomas. I was in the fourth grade, in Mrs. Mulligan’s class. I remember watching the World Series on TV in her classroom.

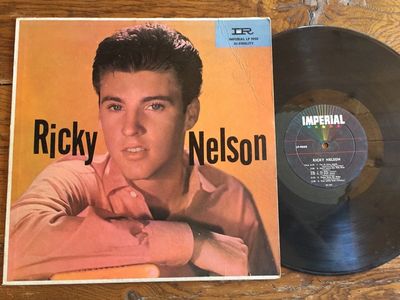

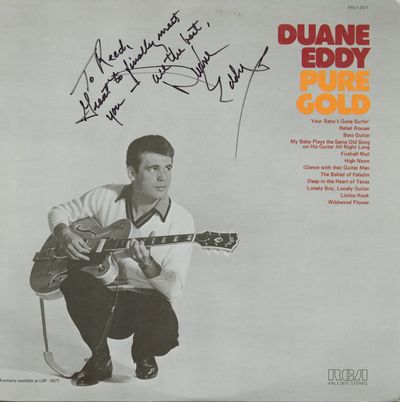

By that point, my father had taken over control of a big corporation, known as Kailing Electric from ailing grandfather Alex. My eldest brother Michael was prepping for college. My other brother, Patrick, ended up babysitting for me. Hanging around with Patrick, who was interested in drag racing, and riding around town with his friends in a ‘52 Ford top-down and eating cheeseburgers and fries at the Milky Way in Milwaukee provided me with an opportunity to hear more and more rock and roll music on the car radio, Rick Nelson and Duane Eddy in particular.

I can still remember, on my birthday in the kitchen of my Shorewood duplex house, my step-grandmother Gertrude presented me with the acoustic guitar that had been owned by my grandfather Malone. In the excitement of the moment, I called my friend Paul Vompomgarden and boasted, “I have a real guitar now.” I felt the need to strum just to prove it.” I had attached pieces of adhesive tape to mark the spots for E, G, and A. I played one string. Receiving that guitar proved to be an inspiration for me. In my own way, I felt a strong spiritual bond to my grandfather, as if my prayer to him had been answered. It many ways, it was receiving his guitar that led me on to other things and that marked a new beginning.

I used to watch Uncle Hugo on TV. Uncle Hugo showed lots of Popeye cartoons. One day, I whirled boiled leaf spinach around a fork, as if it were spaghetti, and then shoveled it down my throat, hoping it could do for me what it would do for Popeye. Coughing up the spinach all over the living room rug, I nearly choked to death. You might say I had become Rick Nelson’s “poor little fool.”

ALL ABOUT ME 3

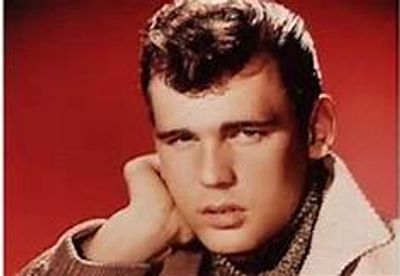

Reed Discovers the Music of Ricky Nelson and Duane Eddy

Rick Nelson was big at the time. I couldn’t wait to see the Ozzie and Harriet Show on TV every week. I also bought a lot of Everly Brothers 45s. Still not adapting to the neighborhood and missing my Huckleberry friend, I took the Greyhound bus to visit Jim Scarry back in Waterford.

One day, I carved up grandfather’s guitar to resemble the one Rick Nelson played on TV. Music had become my escape, and Shorewood was my first confrontation with a bigger city. Living there solidified my love for music.

I built a model airplane in the kitchen of my house. Of course, my brother Patrick showed it to his friends. Patrick had set my airplane on a pillowed seating area by a big picture window. One of his friends, Mac McCarthy, sat down and broke it. I could hear him laughing while I was in bed at night, but I didn’t know what had happened until I got up the next morning.

Ozzie and Harriet Nelson Family (1952)

ALL ABOUT ME 4

Reed Discovers the Music of Ricky Nelson and Duane Eddy (2)

Downstairs, I would sing Rick Nelson and Everly Brothers songs until I was blue in the face. All of sudden, one day I heard a twanging guitar with no vocals on the radio. I thought, “Wow, maybe I don’t need to sing. I could just play guitar.” The artist was Duane Eddy. That experience led me to become not just a Rick Nelson and Everly Brothers fan. Duane Eddy came to play a major role in developing my love for music. I gravitated toward him because I loved the sound of the electric guitar. Once a lady asked my mother, “Where’s Reed?” “He’s alone,” she replied, “he’s got somebody watching him--Duane Eddy (in spirit) on his Victrola.”

ALL ABOUT ME 5

Reed and His Brother, Patrick, See Duane Eddy at the Riverside Theater

Since my brother Mike was gone, Patrick was in charge of watching over me while Mom and Dad attended to whatever they had to do. Pat wanted to go to see Frankie Avalon and other artists at the Riverside Theater on Wisconsin Avenue. To our surprise, Duane Eddy happened to be on the bill. Patrick got my dad to cough up an extra five bucks for a ticket, and Pat brought me along to the show. Pat was my guardian, and I might as well have well been strapped to him. In any case, I was really excited to go, and together we hit the road.

Artists came on stage and performed two or three songs a piece. The same band backed up every vocalist. I became antsy, left my seat, went down to the lobby, and found the door that went to the basement, thinking that it was a way to get backstage to performers’ dressing rooms. Because the foundation of the theater was right on the Milwaukee River, the hallways were dark and humid. In the distance, I saw a light and could hear the distant beat of a single drum, today known as a snare drum. As I approached, the light shined brighter. A light bulb dangled from single wire. A guy with two drumsticks was tuning his drum. I believed I had just met the drummer for Duane Eddy. I asked him if I could be allowed to meet my idol, Duane Eddy. He said, “No way, kid; I think its time to leave.” I walked back to my seat in the balcony thinking I was about to see Duane Eddy perform. I then heard the announcement, “On behalf of WOKY, I introduce to you the one and only Duane Eddy,” who approached the stage with his bright-orange, single-cutaway, 6120 Gretsch guitar and Magnetone amplifier. To my surprise and total letdown, the drummer I just met and talked to was not Duane Eddy’s drummer at all. I had been deceived. Interestingly, many years later, I finally had the chance to meet Duane Eddy and his wonderful wife Dede in person at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland. Upon telling Duane that story, he did remember the venue. Being the country gentleman that he is, Duane said, “Son, I would never let a drummer like that be part of my band; and it would have been a pleasure to have met you.”

While I was still living in Shorewood, my mother bought me my first electric guitar, a Stella acoustic. Unlike my grandfather’s guitar, which was somewhat impaired with a broken tuning peg, my new instrument allowed me to get a grasp on the beginning stages of playing guitar. When I received the guitar, I was so proud of it that I displayed it in the window to for everybody to see. Across the street from us lived Punch Davis, a guy with a cool hotrod. But more important to me, he had a guitar that resembled the one that Rick Nelson played.

ALL ABOUT ME 6

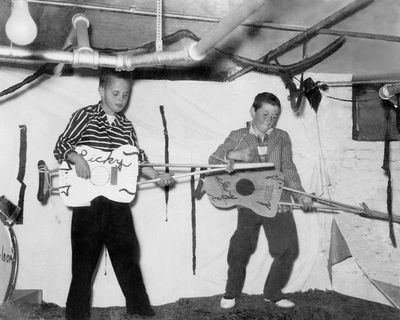

Reed's Basement Ricky Nelson Show

With all this momentum building up, I felt the time was right to get out of my shell and experience the idea of what it would be like to perform. This would be my very first gig. I posed a litany of questions to myself. What is the meaning of performance? Just what would I perform? Since I had no material of my own, the next best thing would be to imitate one of my all time musical idols, Rick Nelson. I was indeed fortunate to have taken advantage of watching him every week on the Ozzie and Harriet Show. This provided me with a strong foundation. In my young mind, I had no visual images of the Everly Brothers or Duane Eddy to draw from.

What was the venue? The venue was downstairs in my basement. And the band? The band on stage consisted of myself playing the role of Rick Nelson, Pat Burgess on drums, and Greg Vompomgarden on guitar (playing the part of James Burton). The actual sound would be provided by Bob Philips, who played the 45 records on my old RCA Victrola. So what did the audience see and hear? I lip-synched and played air guitar to music Bob played on the Victrola placed under the stage. First came the electric shock as Bob placed the needle on the record, then came the hiss, then the music. The effect was heightened by an occasional ungodly grunt of “Ouch” that confounded the audience. Bob, you see, was not properly grounded and experienced some rather uncomfortable electrical shocks.

Finally, there were the refreshments. I pursued them at my all-time favorite soda fountain on Lake Bluff and Oakland Avenue. Meanwhile my brother Patrick, who worked there, served me a hot fudge sundae. Pat spoke up to Mr. Raschke, the pharmacist, “Did you hear Reed is performing the Rick Nelson show in the basement of our house? He was wondering about talking to you about getting some candy refreshments that could be sold at the show. He’s gonna use the profits would to build a soapbox with all the other neighborhood kids.” To my surprise, Mr. Raschke offered me Snickers, Three Musketeers, and various other candies that he sold at the shop for five cents a piece. He let me have them at half price, which was his cost. Mr. Raschke remarked, “I’m glad to help. Good luck with the show. Let me know how it goes.” I was so excited that I ran home to tell all my friends. Then the reality set in, “O my goodness, I’m gonna do a show.”

That show went on without a glitch. The songs were Mary Lou, Bucket’s Got A Hole In It, Poor Little Fool, and It’s Late. To this day, I still have the photo that my mother took on the day of that show at 4437 North Murray Avenue, Shorewood, Wisconsin. Who would have thought that the “Little Warrior” from Waterford, Wisconsin would perform in Shorewood--the big city--in the year of 1957, with the help of all the kids in my new neighborhood. My first performance made $17.35 after expenses. The rest is history.

And by the way, the $17.35 raised from the show provided the kids on Murray Avenue just enough money to pay for materials used to put together our neighborhood soapbox called “The Shark.” A twenty-inch, tin-metal duct was split, nailed to the base of the chassis, and spray-painted black. It was made to look like a shark fin. The Shark was test driven by me at the Lake Bluff School, which provided an incredibly steep downhill asphalt driveway. Unfortunately, the problem was that our meager budget failed to provide adequate materials--i.e. an axle that could withstand the rigors of an out-of-control, downhill ride. Losing the cart’s front left wheel, I ended up rolling over several times. I pledged never to become a famous race car driver. Rather, I found it more comforting and a bit safer to perform as an entertainer.

ALL ABOUT ME 7

Reed’s Frontier Family in Mequon, WI

Somewhere around 1958, my family moved to Mequon. The 40-acre estate we moved into consisted of a summer home that my grandfather and grandmother would live in from Memorial day through Labor day, and also a cottage that my other Grandma Kailing moved into due to my grandfather’s failing health. Much renovation needed to be done, especially in my grandmother’s cottage, which had been built in 1845. Due to the fact that the cottage remained dormant for so long, racoons had made their nesting spot within the walls. The carpenters who were rehabbing the cottage placed a can of sardines near a hole they had cut in the corner of the floor inside one of the upstairs bedrooms in order to draw out the family of raccoons, from which one of the baby raccoons rescued was given to me as a pet. I gave her the name Rosemary Cooney. That raccoon turned out to be one of the best pets I had ever owned, and it was starting to feel like Waterford all over again. Later on, I rescued a part-shepherd, part-wolf stray from the police who were trying to shoot her. That stray wolfdog, which I named Gypsy, also became my pet. Due to fact that there was nothing for miles around, my pets became my frontier family.

There was little family life in my home. My parents were great fans of the local country club, where they were very active and spent most of their time. Mom and Dad had so many social commitments at the Ozaukee Country Club that they were seldom home. Since my brothers had moved on to college, I found myself alone a great deal. I became fascinated by things that fly in the air. For a while, I reverted back to building model airplanes to occupy my time. But once again, I found my escape in music. I soothed the pain of loneliness by listening to records and learning to perform music on the piano by ear, including such songs as Tonight by Ferrante and Teicher and Summerplace, as well as part of Moonlight Sonata. I had fond memories of listening to my Uncle Bob play that haunting yet soothing Beethoven piece when I was a kid.

ALL ABOUT ME 8

Reed Learns to Play the Piano and the Guitar

An unquenchable thirst for music coupled with thoughts of artists like Rick Nelson and Duane Eddy circulating in my mind drove me to learn to play the guitar. I loved playing the guitar. And my guitar had become a sort of security blanket--a shield behind which I could hide. I taught myself to play the guitar off the piano. How? I would first find the chord on the piano, say an E major chord. Then, with the guitar perfectly tuned to the piano and resting on my lap, I would find the E chord on the guitar. That’s right, I learned to play many chords my own way, a tendency that is still reflected in my music. To this day, when I play an E chord, other guitarists sometimes look at the formation of my fingers on the fret board in order to figure out precisely which chord I am playing. You see, having been self-taught, I often reverse the “standard” finger positions.

Another one of my tricks for learning music, especially when teaching myself instrumentals, i.e. Memphis by Lonnie Mack, was to take the old RCA Victrola and slow-down the speed at which the record played from 45 to 33 1/3 rpm. Then I would de-tune the guitar to match the sluggish tone of the slow-playing 45. I could then figure out the song at that speed. Once I felt sufficiently confident, I would simply play the 45 up to speed and re-tune my guitar in order to finish learning the song. This was my method for learning many instrumentals.

Starting to feel at least somewhat accomplished as a musician, yet still in the beginning stages, I discovered that for every bit of success, you do have to pay a price. In my case, that price was being awakened at 2:00 a.m. by my parents. Mom and dad would arrive home from the country club with some of their friends, and the party would move from the club house to our house. Then my mother would say, “Now, Reed, play for the nice people.”

I made a friend in Mequon, Tom Marchese. He had a go cart, so I got a go cart. We used to race up and down the long gravel path that led to my house. Although we were friends, we were very different. Eventually our lives took very different paths. Tom didn’t have much passion for school and chose to walk on the wild side. I, on the other hand, became one of what was then known around here as a collegiate. A few years later, Tom would die tragically at the age of 17.

At the time, I found myself in an awkward stage of shyness as I was entering into the sixth grade. At school, once again I had to make a whole new set of friends; and unlike the urban Shorewood crowd, I found myself adjusting back among the country crowd. My sixth grade teacher at Rangeline School had a habit of assigning lengthy homework assignments to be completed during class time and, occasionally, she would fall asleep. The rumor goes that she had met a new boyfriend and was engaged in some late night extracurricular activities. One day, the class was startled when the book that she used to hide behind while taking a little snooze fell down. She let out a snort, woke up, and said, “Children, keep doing your homework.” Yes, we did a lot of reading and paperwork while she napped. I found that my favorite class of all was music. For one thing, we actually got to leave the classroom. The music area was downstairs. Sometimes we made musical instruments. My favorite project was making a drum out of a cylindrical Quaker Oats box. That year was non-eventful, except for one exciting moment when, at Christmas time, I offered the class its own Christmas tree. Also, during the sixth grade, I started to take guitar lessons. Fred Winter was my teacher on my first electric guitar. I remember having to learn how to play La Spagnola.

On our property were two dense forests of towering evergreen trees, Ponderosa pines and spruces or firs--whatever Christmas trees are made out of. Back in the early 1920s, my grandfather unknowingly planted them too close together. At maturity, these trees soared at least 30 feet into the air. I looked up to see that the top of these trees took the shape of a Christmas tree. I climbed the tree with a saw in my hand, at least 15 feet or higher, depending on how much of the tree I wanted, cut it with the saw, dropped the saw to the ground, held onto the amputated part of the tree, and jumped off. The foliage of other nearby trees acted as a sort of parachute to break my fall as I tumbled to the ground. When I got to the bottom, I pulled the tree out about 20 feet beyond the perimeter of the forest. The next day, I took it to school, and that was our class Christmas tree.

ALL ABOUT ME 9

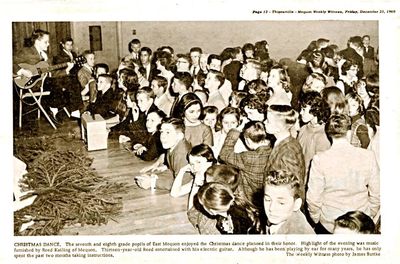

Reed Performs at “The Minstrel Show” and School Dance

Seventh grade, which spanned the years 1960-1961, proved to be more interesting and eventful for me. First, I enjoyed the fact that we moved from one classroom to another; and second, we had two different teachers. One of the teachers, Mr. Althone, proved to be interesting in the fact that he loved to do stage shows. My other teacher was Ms. Sandham. She allowed me to play my electric guitar at our seventh grade dance. That same dance was also open to eighth graders.

Mr. Althone did a show called “The Minstrel Show.” It proved to be quite controversial, because all the students who were involved performed in black face. At the time, Mequon knew no African-American residents, nor did my school have any black students. Unfortunately, the people in the audience didn’t quite grasp the importance of the inclusive message Mr. Althone was trying to promote. One could say he was a little bit ahead of his time. The show received warm reviews.

Ms. Sandham graciously approved when I requested an opportunity to play my electric guitar at the intermission of our seventh grade dance. Even at that time, I believe my teachers saw that my path in life would have something to do with the entertainment world. The night of the big dance, my parents were at the club, of course. Therefore, they asked a friend to pick me up for the event.

In preparation, I took out my finest black slacks, white shirt, jacket and tie, only to notice the slacks needed to be pressed. When I began to use the iron to press my slacks, of course, the phone rang. Lacking experience with this sort of thing, I left the iron on the inside panel of the left leg of my pants. I picked up the phone, and the caller was the people who were supposed to give me the ride. They would be five or ten minutes late. Then I noticed an odor of something burning, dropped the phone, and grabbed the iron off my pants. The steaming hot iron had left the beginning stage of a burn–a light brown outline of an iron--on my good slacks. I figured that the lights would be down in the auditorium and suspected that nobody would notice the difference.

But when I was introduced, sitting on a folding chair on stage, with my trusty guitar in hand, just about to begin my first song, Walk Don’t Run by the Ventures, to my surprise, the house lights went up. People in the audience were seated right up to the edge of the stage. Many of them had never seen or heard an electric guitar before. And there I was. I pulled my legs together to hide the stain and played on. After the first crowd response subsided, I regained my composure and played Freddie King’s Hide Away and Sensation.

The audience was overjoyed, and I shared that same feeling as well that night. Ms. Sandham was one of the chaperones. She came up to me afterwards. I could see in her eyes how proud she was of me. To this very day, I can still see that look and hear her say to me, “Job well done, Reed; you made a lot of people happy tonight. I’m proud of you.”

Eighth grade terrified me. My teachers, Mr. Hoffman and Mr. Ehn, had scary reputations that preceded them. Initially, I was scared to death of both of them. Prior to the start of that school year, I wished I could transfer to St. Cecilia or to any other school. Mr. Hoffman seemed very rough; but in the end, he turned out to be a cool guy. Mr. Ehn had initiated a classroom policy known as Siberia. Going to Siberia meant being kept in during lunchtime recess and having to write down every word in a dictionary, together with the essence of its definition. Afterwards, he would quiz us on the meaning of each word we had written. If we missed too many words, we had to repeat the process the next day. I quickly learned to work slowly in order to keep down the quantity of work. By the end of eighth grade, I reached the age where the girlfriend thing began kicking in. Tuggerball was the big sport.

Musically, things were fairly non-eventful for the most part. I began studying music more formally, but was not really having much success. I was taking piano lessons from Tommy Sheridan, the well-known, high-society dance band pianist, who was also a respected music teacher. My mother arranged for the lessons with Tom, and I can still remember my first song, Beginner’s Boogie. Also at the same time, I was flirting with writing my own original songs. I came to realize that I was learning more from Tommy by memory than I was from reading the printed musical notation. This fact also became apparent to my parents, and they had a meeting with Tom. “He’s not reading the music,” my mother complained to Tom. To mom’s and dad’s surprise, Tommy told them, “Reed is performing from lead sheets (documentation) of the songs. Leave Reed alone regarding the note-reading aspects of music, interfering now could interfere with his innate ability to compose.”

Looking back at that time, I discovered why I had a problem reading music. So much of music theory was based on mathematics. In school, I had trouble with math. Even today, people still ask me the same question. “If you can’t read music, then how do you compose?” To this, I reply, “I write songs. I don’t read the music; I just look at the pictures.” Yes, I had my own vision of what the music is supposed to be. Also, as I recall that time in my life, I was becoming increasingly attracted to the guitar, which (as I mentioned earlier), I had learned off the piano.

ALL ABOUT ME 10

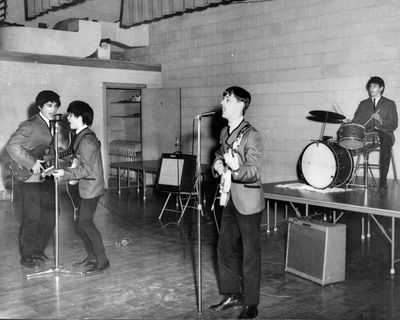

Reed's "Beatles" Performance

Still tinkering with music, I moved on to my freshman year of high school. It was during the summer of 1962 that I met Fred Hadler, who was experimenting with the drum set that he had. Fred lived on Sunnydale Drive in Thiensville. I would bring my guitar and small amplifier, and we would jam in the basement of his house. We would try to impersonate whatever song was happened to be popular on the radio at the time. After a while, it became evident that just playing together for ourselves was not very satisfying. That fall, we decided to expand our horizons.

ALL ABOUT ME 11

Reed's "Beatles" Performance 2

It wasn’t until February of 1963, when the Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show for the very first time, that I was totally hooked. I can still remember walking into the school cafeteria for a record hop. I walked up to a lunch table strewn with different LPs. I saw the “Meet the Beatles” album and became totally mesmerized. It was at that point that an idea came to me. Why not put together a mock Beatles group as a skit for the upcoming American Field Service (AFS) variety show? Joining myself and Fred Hadler were Jerry Schneider, playing the role of George Harrison, and Rick Wolf as the McCartney character. Fred played Ringo, and I played John Lennon. We went so far as to get Beatle wigs that were popular at the time, as well as Beatle collarless jackets. I believe the style became called a Nehru jacket. Fred and I were the only two that actively made any music. Rick and Jerry just mimicked doing so both instrumentally and vocally. And in the group, I was the only one who had genuine long hair rather than just a wig. There’s more coming on this later.

The school was so concerned about possible charges of trademark infringement over unauthorizedly using the Beatles name, that the name “Cleolatra Four”(Beatles in Latin) appeared in the printed program. Both the Friday and Saturday performances of this event were extremely successful. The audience threw jelly babies (aka jellybeans) on stage, just as enthusiastic fans had thrown at the Beatles. And by the way, getting hit by flying jellybeans can hurt.

ALL ABOUT ME 12

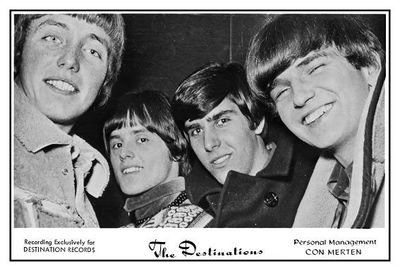

Reed Gives Birth to the Destinations

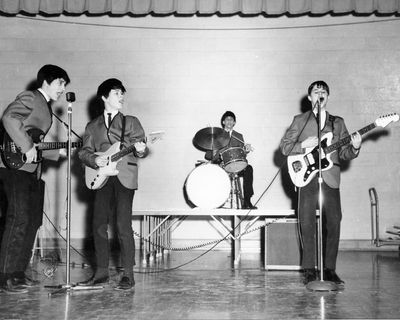

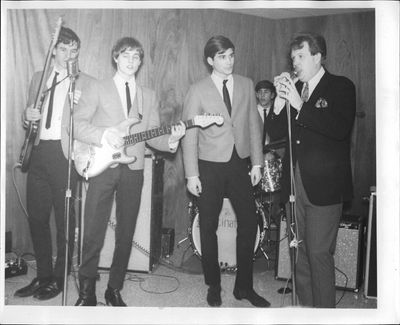

After the Saturday night’s final performance, we were asked to perform for a post-show party. That marked the birth of what would become known as “The Destinations.” From that point on, Rick Wolf became the lead singer, I became the rhythm/lead guitarist, and Fred Hadler was the drummer. From time to time, various people filled in on bass guitar. Jon Paris, a fine drummer, occasionally subbed for Fred.

For a while, we also had a member whose name was Mike Davidson, son of Walter Davidson of Harley-Davidson notoriety. Mike, nicknamed Harley, wanted to be part of the band. He was a good friend who bought a Fender Bassman amp and an SG Gibson bass guitar. We thought, “Wow, what a cool guy.” He had all the gear. We started getting phone calls from the neighboring schools, such as St. Cecilia in Thiensville, to play to play for Catholic Youth Organization (CYO) dances. Unbeknown to the audience, Mike would turn on his amplifier, displaying the red light. Actually, he kept the amp on standby. Mike turned his back to the audience, gave the physical appearance of playing, and remained as quiet as a church mouse. I found out later on that Stew Sutcliffe, the close friend of John Lennon in the Beatle’s early days, had essentially done the same. Unfortunately, Stew died of a brain disorder due to a fight. In any case, Mike’s career with our band was short lived.

In the summer of 1963, we auditioned several bass players. At this point in time, I can’t recall who they were. We finally settled on Bruce Robertson as bass player and added Sid Rice on keyboards. It was not unusual to interchange musicians based upon their availability. Especially when Bruce could not travel ninety miles away from Milwaukee to Madison in order to play frat-house type jobs, David Zucker filled in on bass guitar. David and his brother, Jerry, later became very successful film makers. They are well known for their movie Airplane and Naked Gun (with Leslie Nielsen and O.J. Simpson). We also had other substitutes, including Tom Wittenberg from Mequon and Sam Friedman from Shorewood. As time moved on, Bruce became more of a fixture in the Destinations as the band’s popularity grew. My brother Patrick managed the band at that time. One of our equipment guys, Dave Spaulding, also acted as our accountant. He was a very close friend and coordinated well with Patrick.

It’s interesting to note at that time, top-forty radio was exploding with sounds of the British Invasion, and it seemed that every high school in the Milwaukee and its outlying area had its own favorite local band. Prospects of venues to play--including CYOs, nightclubs, and so on--made the situation very different from today. There were endless opportunities to perform and make good money. I was consumed by the music; on the other hand, many succumbed to the money.

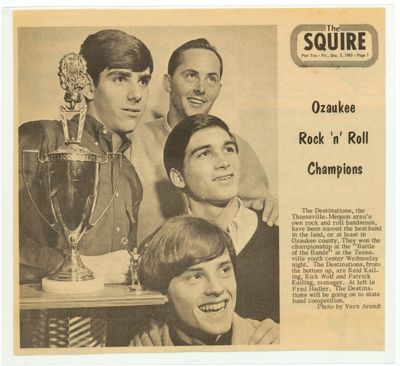

ALL ABOUT ME 13

Reed and the Destinations Win the Milwaukee Sentinel’s Battle of the Bands

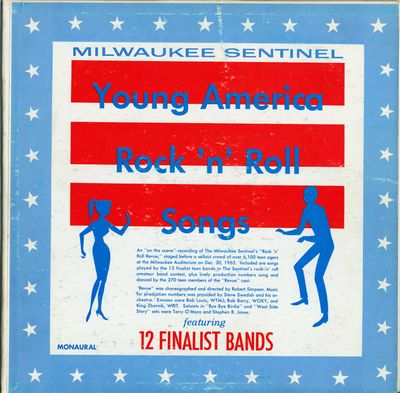

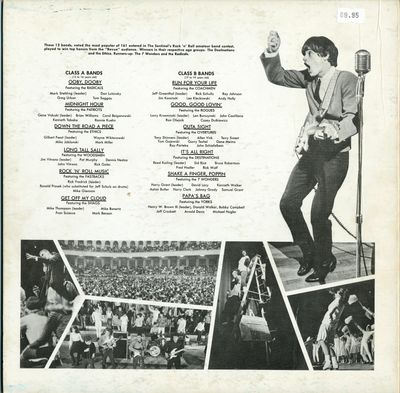

In 1964, the band became increasingly popular and financially successful. We geared up for the 1965 Milwaukee Sentinel newspaper’s Rock ‘n’ Roll amateur band contest. Up to this point, we had previously engaged in 17 local battle-of-the-bands contests and never lost one. The Milwaukee Sentinel’s battle of the bands was a state-wide competition. It is estimated that over 500 regional bands aspired to participate in the competition. One hundred and sixty one bands actually entered the contest. Initially, bands were eliminated via ballots found in the newspaper. Eventually the competition was reduced to just 24 bands. Then live performances voted on by local deejays narrowed the contenders down even further to 12. These were broken down into two age categories, six in the Class A (13 to 16 years old) group and six in the Class B (17 to 19 years old) group. The battle of the bands was staged before a sellout crowd of over 6,100 teenagers on December 30, 1965. The audience vote at the Milwaukee Auditorium on Kilbourne Avenue brought us the number one slot for our performance of “It’s All Right.”

ALL ABOUT ME 14

Reed and the Destinations Win the Milwaukee Sentinel’s Battle of the Bands

A highly collectable LP was made of the entire event. The band’s popularity then exploded regionally, and it became quite successful financially as well. Although the members of the band were still minors, we played local clubs including the Scene, Gallagher’s, and a variety of others, as well as a number of colleges. Also, at this point in time, Sid Rice was replaced by Rick Sorgel, a fellow Mequonite who I used to give guitar lessons to.

ALL ABOUT ME 15

Reed and the Destinations Win the Milwaukee Sentinel’s Battle of the Bands (2)

One of the more demoralizing events took place at the Milwaukee Arena. Because of our notoriety after winning the Sentinel’s battle of the bands, we were invited to perform at the half time of the Harlem Globetrotters Show. That same evening, after our performance, which lasted a total of about 15 minutes, we were to go to Dave Kennedy studios to record our first single produced by local WRIT deejay, King Zabornik. Excited about recording for the first time, our egos were shattered and at least momentarily, and the adventure came to a screeching halt. Upon playing for the Globetrotters’ intermission, in front of approximately18,000 people, with our dual Showman amps--a total of six--cranking out the Rolling Stone’s Nineteenth Nervous Breakdown at top volume, the audience responded with a massive resounding “B-o-o.” Upon leaving and heading toward the recording studio, we had to redefine our sense of self-confidence, and that was a real learning experience. One of the two songs we recorded that night was an original titled It’s All Over; the other was called So Cry No More, its lyrics were written by Mary O’Brien, a girl I dated on a couple occasions back in high school. Speaking for myself, I definitely believe that what occurred after that event marked a cornerstone in my career.

ALL ABOUT ME 16

Reed Composes “Hello Girl”

Yes, the spring of 1966 was a major turning point in the future of the band. Rick Wolfe, the Destinations’ lead singer, had led us to believe that he would attending the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM) in the fall. This, we thought at the time, was great news. Rick’s presence locally would allow us to remain together as a group. Finally, I graduated from high school, but not without at least some drama. Prior to winning the Sentinel’s Battle of Bands, our band was gaining notoriety and things were taking off. I started growing my hair longer. I kept getting warnings from the Vice Principal who said, “You can’t be doing this.” First, I started wearing bangs in the front, then my hair was getting longer in the back; and soon it was getting to be a full head of hair. The Vice Principal approached me and said, “You cannot wear long hair, and you have to leave school.” I was suspended for a day or so. My parents got involved; they were getting quite ticked off at the school. Shortly thereafter, the Battle of the Bands happened, we won, and guess who got to keep his long hair! The story made the newspaper; and I still have the articles and pictures. During the Summer of 1966, I wrote the song Hello Girl.

ALL ABOUT ME 17

"With You" Is Chosen for the Flip Side of "Hello Girl," Rick Wolfe Leaves the Destinations

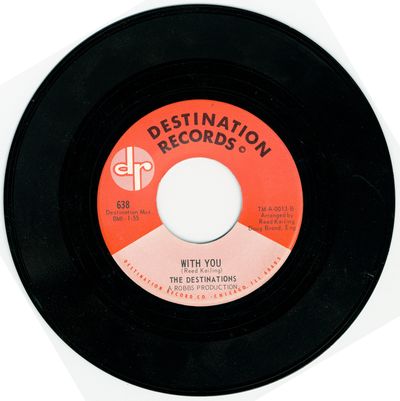

What eventually would become the flip side of the Destinations’ 45, a song called With You, had already been written that previous winter, while sitting at a blonde spinet piano at Rick Sorgel’s house during a brutal snow storm.

The summer progressed, and we continued to play gigs at the Scene, Gallagher’s, and other sites too numerous to list here. Then all of a sudden, Rick Wolfe our lead singer, confronted the band. He said, “You need to talk to my parents.” “Fine,” we replied. At the time, Bill Wilson was our bass player, Fred Hadler was the drummer, and Rick Sorgel played keyboards. Fred, Bill Wilson, Rick Sorgel, and I went over to Rick Wolfe’s house to speak to his parents. To our surprise, they had no idea why we were there. I indicated that their son, Rick, wanted us to speak with them. At about the same moment, Rick walked out the door to go on a date, never intending to tell us he was going to college at Colorado State.

ALL ABOUT ME 18

Reed Becomes Destinations' Lead Singer

We were crushed. Without a lead singer, the band had temporarily broken down. In August of 1966 sitting at Rick Sorgel’s house, we were all wondering what we were going to do. Then Fred Hadler said, “Hell, Reed, why don’t you become the Destinations’ lead singer?” I replied, “I’ve never sung lead; I’m a background singer.” Fred responded, “You’ve got a great voice.” All the guys concurred with Fred. We went down to the basement, and I tried it out. Henceforth, I became the Destinations’ new lead singer.

The Destinations had become a very valuable commodity. We were making good money, averaging $800 a week per guy, playing all the hot spots. Plus, we had two equipment guys. One member of the group, my personal Judas Iscariot, sought to sell me for thirty pieces of silver. Yes, for his own personal gain, Judas convinced Fred, the band’s co-founder, and its other members that my presence in the band coupled with having my brother, Patrick, as the band’s manager constituted a conflict of interest. Judas caused the members of the group to question where all the money really was going. In reality, having Patrick as our manager was one of the best deals and biggest benefits the band had. Judas, on the other hand, had a two-fold personal agenda. First, he wanted to increase his own control over the band financially as its bookkeeper; and second, he wanted Con Merton to replace my brother as manger of the band.

At that time, Con Merton managed just about every band of any notoriety, including the Robbs, the Messengers, and the Next Five. And Con badly wanted to get a hold over the Destinations as well. Judas had been in contact with Con Merton, and tried to convince the other members of the band that Con should manage the Destinations. At one point, I confronted my friend Fred Hadler, since he and I had started the whole Destinations thing. I asked Fred why this other member, who we had invited to join us, would now be dictating our future. I came to realize that this was a mutiny, and I had been given an ultimatum. The damage ran so deep that my alternatives were either to accept a new manager or lose an entire band. One of the hardest things I ever had to do was tell my brother, Patrick--my former babysitter--that his services were no longer required as the Destinations’ manager. Henceforth, Con Merton became the manager, and the band took a new direction.

ALL ABOUT ME 19

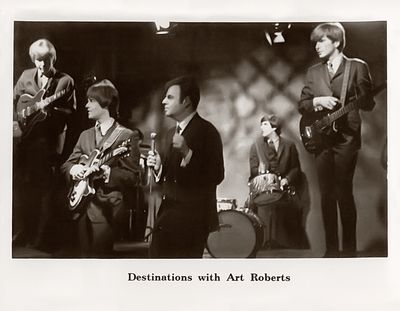

Reed and the Destinations on Art Roberts’ Swinging Majority Show

The Destinations started to record the songs I had written earlier. These recording sessions occurred at RCA Studios, at Navy Pier in Chicago. The idea was that the guys would lip-synch to the recordings when the group performed on the Art Roberts Swinging Majority show. Among the songs we recorded at that time were Hello Girl, With You, Colleen (written for Colleen Covert, one of my high school girlfriends), It’s All Over, Baby (written at school during study hall), Remember When (written in collaboration with my mother over a cup of tea, as she reminisced about meeting my father), and Whole Lotta Lovin'.

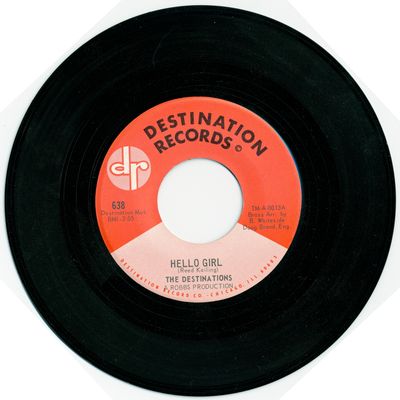

Yes, it was during those sessions at Navy Pier that we recorded a demo of Hello Girl. After appearing on Art’s show for the very first time, he really liked the band and asked us to be a regular every week. He mentioned to Con Merton that it would be advisable for the band to come out with a record. We all concurred that Hello Girl would make a strong plug side for a 45.

Dee Donaldson, of the Robbs fame–also managed by Con Merton--came on board as producer. The Hello Girl single was recorded at Chess Studios on South Michigan Avenue, the same highly- acclaimed studio where the Rolling Stones recorded their first album. The Guess Who also recorded there. Hence, Hello Girl was as born on the Destination label, owned by Jim Golden and Bob Monaco. Hello Girl became a regional hit.

Back to the Art Roberts ordeal, Art’s Swinging Majority show aired live every Saturday afternoon for one hour, from 4:00 to 5:00 p.m. on WCIU-TV at the top of the Board of Trade Building on La Salle Street. Art held a unique position as Program Director of WLS Chicago radio. He could attract almost any band that was playing anywhere in the Chicago vicinity because of the power he wielded. I’m reasonably certain that local bands like the American Breed, Buckinghams, Shadows of Knight, New Colony Six, as well maybe Chicago and Aliota, Haynes, and Jeremiah made guest appearances on Art’s show. Then, there were also such groups as Traffic, Martha and the Vandellas, as well as a little band from Gary, Indiana managed by its father, Joe Jackson. That band was known as the Jackson Five. Interestingly, the Jackson Five and the Ides of March appeared on the same episode, well before either band had achieved national recognition. Another group that performed on Art’s show was the Grass Roots, a group with which I became friendly.

Interestingly, the second time that the Grass Roots appeared on the show, Warren Entner and I were talking in what was a sort of dressing room/closed-off hallway right next to the studio, which was approximately 25 or 30 feet by 30 feet. There was a doorway off to the side, and there was a ten-piece Hispanic band on, wearing mint-green tuxedos and puffy white shirts. The band was lip-synching a song. Warren said, “Hold it, Reed, I want to hear this song.” We both listened attentively. Afterwards, the Grass Roots were flying back to Los Angeles. Warren asked the lead singer of the Evergreen Blues Band for a copy of the group’s 45 that had previously been released locally. Warren commented on how much he liked the song. Upon returning to Los Angeles and getting clearance to record the song, which was produced by Steve Barri on the ABC Dunhill label, that song reached #2 slot on the national charts and became the Grass Roots’ biggest hit. It was the Grass Roots’ signature song, Midnight Confessions. At that time, never in my wildest dreams did I imagine that I would eventually become a member of that band.

Popularity of the Destinations surged. We were performing throughout Wisconsin, Michigan, and Illinois. Largely due to playing on Art’s TV show, we gained a new level of exposure and success. I also made some important contacts and met some great people, including my lifelong friend, Rick Wozniak. The only drawback to doing Art’s show was the two-hour drive to play for one hour live, and then having to return to Wisconsin to perform that same night. Because of the frequent traveling from Milwaukee to Chicago and back, Dick Keskey, the guy who drove my car back and forth really got gutsy on the road. My car, a Corvair Spider, was so light that on one occasion, Dick actually drafted the suction of a Greyhound bus traveling in front of us and took his foot of the gas. Later he commented on how stupid that was, because we were literally traveling four feet behind the bus. Sometimes he would drive in excess of 105 to 110 miles per hour just to see how much time he could cut off the trip. One time, we were so late that Bill Wilson, our bass player who liked drinking beer a lot, was forced to relieve himself in a beer can. There was just no time and no place to stop. As every beer drinker knows, you don’t buy beer, you just rent it.

ALL ABOUT ME 20

Reed and the Destinations on Art Roberts’ Swinging Majority Show (2)

In 1968, the Destinations had achieved great success, but the Judas character in the band had motives of his own. In concert with the wishes of the manager Con Merton, this member of the band convinced the other members that maybe it was time to bring in another guitar player. Judas and Con staged a power play in order to gain more control over the band’s success and finances. Fred coined the phrase “Reader the Leader,” a line that caught on with the other guys in the group. I, you see, was the group’s most responsible member, as well as the one who wrote all the original music and who gave the band some sense of direction.

Having my own personal suspicions come true proved very disturbing. Walking into a rehearsal at Rick Sorgel’s house, I felt a very cold vibe in the air. I looked at Fred Hadler; Fred look at me, head down; he would not make eye contact with me. Yes, Judas had even won over my friend Fred. I said, “I get it now.” Then I looked at Judas, the perpetrator who had orchestrated this whole thing and asked, “So, you want this to be your band?” Judas replied, “I think it’s time for us to move on musically.” I asked Fred, “How can this be happening? Why are you going along with this? You and I started this whole thing.” Fred remained silent. I said, “OK, fine.” We had a lot of equipment I could have taken with me. Instead, I took my guitar and amplifier and walked out.